Book Writing 101: Everything You Need To Know About Dialogue

No matter what genre you write in, learning how to write dialogue effective is an essential part of any writer’s toolkit. Poorly-written dialogue can be distracting or worse —it could cause your readers to close the book in disgust. However, dialogue that is done well can transform your characters into truly believable people and you readers into satisfied, lifelong fans. Of course, the best kind of dialogue isn’t just believable conversation between characters. Good dialogue provide exposition, involves distinct language true to the voice of the speaker, and most importantly, helps move the story along. Dialogue is directly tied to pacing, plot, and tension, and can make or break your story just as much as lame characters or a sagging plot.

This guide is separated into three parts for your convenience — Dialogue Basics, Punctuating Dialogue, and Dialogue Tags —and is filled with cheat sheets, quick-reference-guides, examples, and more to help you with your writing!

This blog post was written by a human.Hi Readers and writerly friends!

This week in Freelancing, we’re discussing dialogue tags and how to properly format them. Consider this as your new intensive, all-encompassing guide for doing fictional dialogue well.

No matter what genre you write in, learning how to write dialogue effective is an essential part of any writer’s toolkit. Poorly-written dialogue can be distracting or worse —it could cause your readers to close the book in disgust. However, dialogue that is done well can transform your characters into truly believable people and you readers into satisfied, lifelong fans. Of course, the best kind of dialogue isn’t just believable conversation between characters. Good dialogue provide exposition, involves distinct language true to the voice of the speaker, and most importantly, helps move the story along. Dialogue is directly tied to pacing, plot, and tension, and can make or break your story just as much as lame characters or a sagging plot.

This guide is separated into three parts for your convenience: 1) Dialogue Basics, 2) Punctuating Dialogue, and 3) Dialogue Tags—and is filled with cheat sheets, quick-reference-guides, examples, and more to help you with your writing! (This post took me a long time to write, so if you found it helpful, please consider leaving a comment and sharing this with your writerly friends!)

Of course, this is just my own experience as well as examples of other writers who have done dialogue well, but this is by no means a rulebook for dialogue. I’m simply a proponent of the idea that if you know the rules of the writing world well, you can effectively break them well.

Dialogue Basics

Enter late, leave early.

If you’ve been around the writing world for a moment, you might have heard this phrase tossed about when discussing scenes, pacing, and dialogue. It’s a helpful saying for remembering to start a scene at just the right time instead of too early or too late.

Alfred Hitchcock once said that “drama is life with all the boring bits cut out.” Hinging on that, you could say that good dialogue is like a real conversation without all the fluff, and one of the best/easiest ways to cut out that boring fluff is to enter the conversation as late as possible.

Think about it: How many times have you heard someone in real life or in media say, “I hate small talk.” It is the same for your readers. They don’t want to be there for every single “Hi, how are you doing today?” or “I’m doing great, how are you? Thanks for asking. The weather is lovely, isn’t it?” This is a fine and good, but its not interesting dialogue, and it’s highly unlikely that this would move any story’s plot along in a meaningful way. The same goes for other kinds of small talk that usually occurs at the beginning and end of a scene. In order to avoid this kind of slow-paced dialogue, simply enter late and leave early.

Keep dialogue tags simple.

Dialogue tags are the phrases in writing that indicate who is speaking at any given time. “I want to write a book” Layla said. In this case, “I want to write a book” is the dialogue and “Layla said” is the tag. Of course, there are plenty of other dialogue tags you could use besides “said,” such as “stated,” “exclaimed,” or “declared” and so on. When writing dialogue, you generally should keep these elaborate tags to a minimum. Think of it this way, to the reader “said” is boring and simple, but its virtually invisible. Readers expect you to use “said” and because of this, it isn’t distracting to the reader.

Remember the KISS method —Keep It Simple, Sweetie? Remember that for dialogue tags. It’s always better to air on the side of caution than risk potentially distracting your reader with overly complicated, elaborate or convoluted dialogue tags.

As American novelist and screenwriter Elmore Leonard put it:

“Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But ‘said’ is far less intrusive than ‘grumbled,’ ‘gasped,’ ‘cautioned,’ ‘lied’” (Leonard 2021).

“Intrusive” is the operative word here. You want to bring readers into your scene and make them feel like firsthand observers, like one of the characters in the background, without drawing attention to the fact that they’re reading a book. Wordy dialogue tags are a surefire way to yank your readers out of the immersion of a story and snap them back to reality. When you raid your thesaurus for fancy dialogue tags, you risk taking readers out of the scene for a fleeting display of your verbal virtuosity. This is true for any writing where you use convoluted language where you would be better served using simple language instead. If it serves a purpose to use uncommon or elaborate verbiage, then by all means, do so, but if its just for the sake of using big words, the practice of using “wordy” language is best avoided.

Additionally, in some instances, dialogue tags can be removed altogether. If there are only two or three people present in a conversation, dialogue tags aren’t always necessary to keep track of the speaker, especially if their voices are distinct convey a character’s personality to the reader.

Descriptive action beats are your friend.

Action beats are descriptions of the expressions, movements, or even internal thoughts that accompany the speaker’s words, and are included in the same paragraph as the dialogue to indicate that the person acting is the same person who is speaking. Action beats help illustrate what’s going on in a scene, and can even replace dialogue tags, avoiding the need for a long list of lines ending in “he said,” or “she said.”

Check out the fourth part of this guide for an example of how to use action beats to strengthen and vary your dialogue structure.

Character voices should be distinct.

Another key aspect of writing realistic and engaging dialogue is make each character sound distinctly like “themselves.” This employs the use of a number of different linguistic elements, such as syntax and diction, levels of energy and formality, humor, confidence, and any speech-related quirks (such as stuttering, lisping, or ending every sentence like it’s a question). Some of these elements may change depending on the circumstances of the conversation, and especially when it comes to whom each person is speaking, but no matter what, there should always be an underlying current of personality that helps the reader identify each speaker.

Example: Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the very first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice, readers encounter Mrs and Mr. Bennet, the former of whom is attempting to draw her husband, the latter, into a conversation of neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.” (Austen 2002)

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character and is never simple or convoluted. Readers instantly learn everything they need to know about the dynamic between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip.

Develop character relationships.

Dialogue is an excellent tool to demonstrate and develop character relationships throughout your story. Good dialogue establishes relationships, but great dialogue adds new, engaging layers of complexity to them.

One of the best ways to ensure your character’s dialogue reflects their personalities and relationships is to practice some dialogue writing exercises. It’s likely that you won’t actually end up using the products of these exercises in your writing, but they’re an easy, low-pressure way to practice developing your characters and their relationships to one another.

For this kind of practice, I’ve found that exercises like “What Did You Say?” are particularly helpful.

Pretend three of your characters have won the lottery. How does each character reveal the big news to their closest friend? Write out their dialogue with unique word choice, tone, and body language in mind.

If the lottery isn’t interesting enough, consider changing things up. Maybe three of your characters have a role to play in a murder investigation. Each one knows a different take on what happened. Lottery or murder investigation aside, developing your character’s relationship will teach you more about your characters themselves, their stories and circumstances, and how to write dialogue that best fits within that framework.

Find similar exercises here.

Developing character relationships alongside and through dialogue is an excellent opportunity to work on both simultaneously. In this exercise, there are a number of characteristics that will affect how each character perceives and delivers the news that they’ve won the lottery (or that they’ve been involved in a murder investigation).

These characteristics might include whether a character:

Is confident and outgoing vs. shy and reserved

Takes things in a lighthearted manner rather than being too serious

Has lofty personal aspirations or doesn’t

Couldn’t care less or wants to help others

Thinks they deserve good things or not

Carefully consider each of your characters and which of these categories they fall into. This should help you determine how they all relate and react to each other in the context of such news.

Show, don’t tell.

We’ve all heard this slice of writing advice, probably more times than we can count, but it’s for good reason. Much like the “enter late, leave early” saying, you’ve probably seen or heard this phrase making rounds throughout the writing world. It’s a sliver of advice that creatives like to use as a buzz phrase in writing communities, but there may be a golden nugget of wisdom to be found in it.

Readers enjoy making inferences based on the clues the author provides, so don’t just lay everything out on the table. This doesn’t mean be cryptic —on the contrary. It basically means you should imply information rather than outright stating it.

Take the dialogue below for example. Even if this is the first instance the reader encounters of Jones and Walker, its easy to deduce that they are police officers who used to work together, that they refer to each other by their last names, and that Jones misses Walker — and possibly wants him to come back, despite Walker’s intentions to stay away.

Hey, Jones. Long time no see.”

“Heh, Yeah, Walker, tell me about it. The precinct isn’t the same without you.”

“Well, you know I had good reason for leaving.”

“I do. But I also thought you might change your mind.”

However, cloaking this information in dialogue is a lot more interesting than the narrator simply saying, “Jones and Walker used to work together on the force. Walker left after a grisly murder case, but now Jones needs his help to solve another.”

Of course, sometimes dialogue is a good vehicle for literally telling — for instance, at the beginning or end of a story, it can be used for exposition or to reveal something dramatic, such as a villain’s scheme. But for the most part, dialogue should show rather than tell in order to keep readers intrigued, constantly trying to figure out what it means.

Bounce quickly back and forth.

When writing dialogue, it’s also important to bounce quicky back and forth between speakers, like in a tennis match. Consider the ping-pong pace of this conversation between an unnamed man and a girl named Jig, from Hemingway's short story, "Hills Like White Elephants".

It might seem simple or obvious, but this rule can be an easy one to forget when one speaker is saying something important. The other person in the conversation still needs to respond. Likewise, a way to effectively break this rule is to intentionally omit the other character’s response altogether if the plot warrants it. Sometimes, leaving the other character shocked proves to be just as effective on the reader.

On the other hand, you don’t want lengthy, convoluted monologues unless its specifically intended and needed to drive the plot forward. Take a close look at your dialogue to ensure there aren’t any long, unbroken blocks of text as these typically indicate lengthy monologues and are easily fixed by inserting questions, comments, and other brief interludes from fellow speakers.

Alternately, you can always break it up using small bits of action and description, or with standard paragraph breaks, if there’s a scene wherein you feel a lengthy monologue is warranted.

Try reading your dialogue out loud.

It can be tricky to spot weak dialogue when reading it on the page or a computer screen, but by reading out loud, we can get a better idea of the quality of our dialogue. Is it sonically true to the characters’ distinct voices? Is it complex and interesting, conveying quirks and personality beyond plot? Does it help drive the plot in a meaningful way or is dialogue being used to fill space? If it is the latter, it should be removed, but more on that next.

For instance, is your dialogue clunky or awkward? Does it make you cringe to hear it read aloud? Do your jokes not quite land? Does one of your characters speak for an unusually long amount of time that you hadn’t noticed before, or does their distinct "voice" sound inconsistent in one scene? All of these problems and more can be addressed by simply reading your dialogue out loud.

Don’t take my word for it, take John Steinbeck’s! He once recommended this very strategy in a letter to actor Robert Wallston: “If you are using dialogue, say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.”

Remove unnecessary dialogue.

Dialogue is just one tool in the writer’s toolbox and while it’s a useful and essential storytelling element, you don’t have to keep all of the dialogue you write in your first or second drafts. Pick and choose which techniques best tell your story and present the interior life of your characters. This could mean using a great deal of dialogue in your writing, or it might not. Carefully consider your story and the characters and whether or not it makes sense for them to have dialogue between one another in any given scene. Just because dialogue can be brilliant, doesn’t mean it’s always integral to a scene, so feel free to cut it as needed.

Format and punctuate your dialogue properly.

Proper formatting and punctuation of your dialogue makes your story clear and understandable. Nothing is more distracting or disorienting within a story than poorly formatted or improperly punctuated dialogue —well, except for an excess of wordy dialogue tags instead of “said,” but I digress! Likewise, knowing when to use quotation marks, where to put commas, full stops, question marks, hyphens, and dashes will make your text look polished and professional to agents and publishers.

How to format dialogue:

Indent each new line of dialogue.

Put quotation marks around the speech itself.

Punctuation that affects the speech’s tone goes inside the quotation marks.

If you quote within a quote, use single rather than double quotation marks.

If you break up a line of dialogue with a tag (e.g. “she said”), put a comma after the tag. However, if you put a tag in between two complete sentences, use a period.

Speaking of tags, you don’t always need them, as long as the speaker is implied.

If you start with a tag, capitalize the first word of dialogue.

Avoid these major dialogue mistakes.

Tighten up your pacing and strengthen your dialogue by avoiding these common dialogue issues. Although the differences in some of these examples are subtle word choice, usage frequency, and arrangement play a big part in dialogue delivery. Consider how these small changes can make a big difference in your writing.

Too many dialogue tags

As you might have guessed, the most contradictory advice you can receive and most egregious errors you can make when writing dialogue have to do with dialogue tags. Do use them. Don’t use them. Don’t use “said.” Do use “said.” Do use interesting tags. Don’t use too elaborate tags. How does the lowly writer win?

Consider this: good storytelling is a delicate balance between showing and telling: action and narrative. So, how does one do dialogue well? Craft and maintain a sustainable balance between action and narrative within your story. I can’t tell you when and when not to use elaborate dialogue tags or when to cut tags out altogether, but I can suggest that when you examine your dialogue, keep this idea in mind and consider it when you sense the balance of action and narrative has skewed slightly (or dramatically) to one side or the other.

Constantly repeating “he said,” “she said,” and so on, is boring and repetitive for your readers, as you can see here:

So, keep in mind that you can often omit dialogue tags if you’ve already established the speakers, like so:

One can tell from the action beats, as well as the fact that it’s a two-person back-and-forth conversation, which lines belong to which speaker. Dialogue tags can just distract from the conversation — although if you did want to use them, “said” would still be better than fancy tags like “declared” or “effused.”

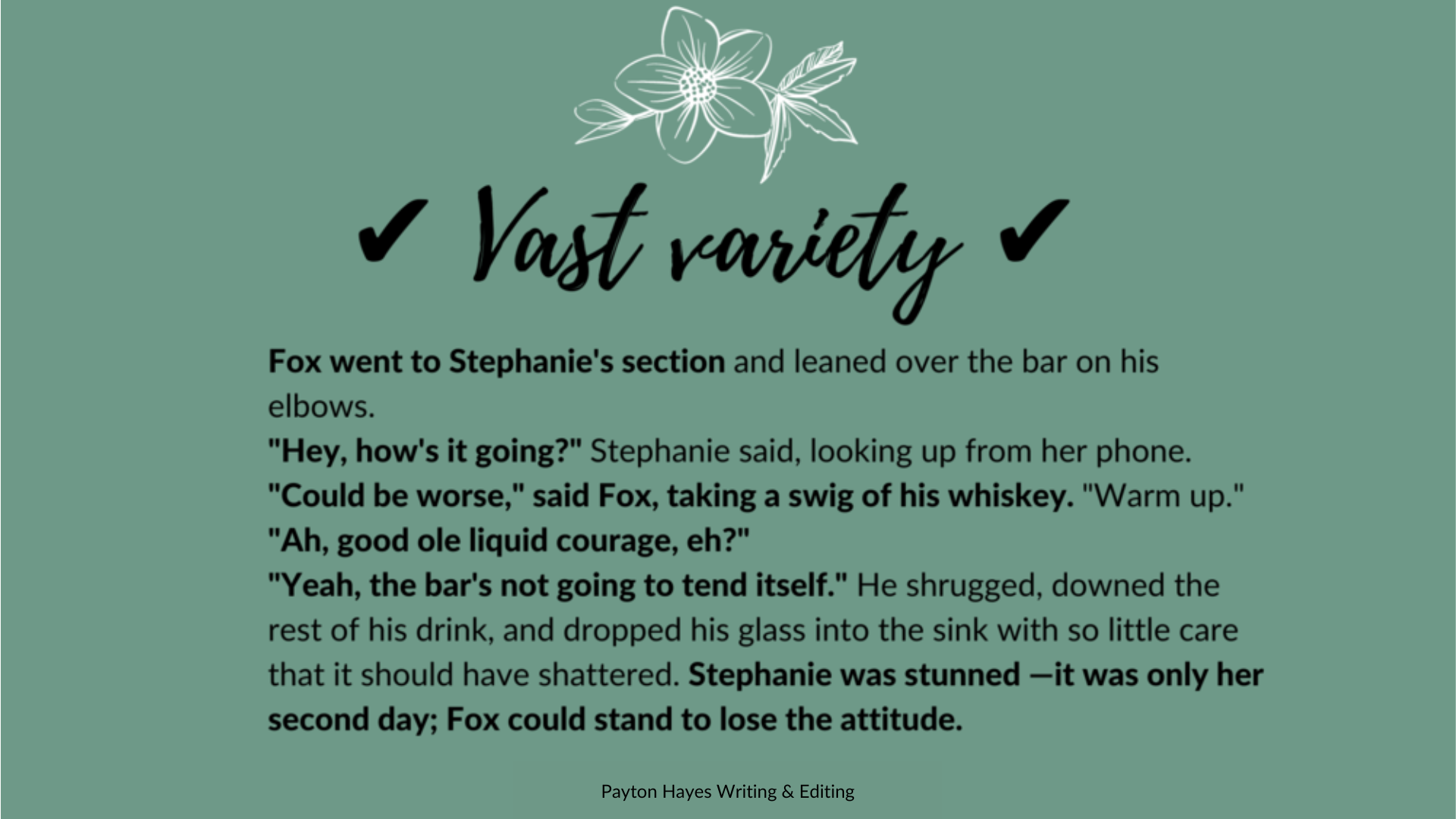

Lack of structural variety

Much like the “too many tags” issue is the lack of structural variety that can sometimes arise in dialogue. It’s an issue that most commonly presents itself in narrative but can occur in dialogue as well. Not sure what I’m talking about? Take a look at these sections again:

Now, action beats are great, but here they’re used repeatedly in exactly the same way — first the dialogue, then the beat — which looks odd and unnatural on the page. Indeed, any recurrent structure like this (which also includes putting dialogue tags in the same place every time) should be avoided.

Luckily, it’s easy to rework repetitive structure into something much more lively and organic, just by shifting around some of the action beats and tags:

Another common dialogue mistake is restating the obvious — i.e. information that either the characters themselves or the reader already knows.

For example, say you want to introduce two brothers, so you write the following exchange:

This exchange is clearly awkward and a bit ridiculous, since the characters obviously know how old they are. What’s worse, it insults the reader’s intelligence — even if they didn’t already know that Sherri and Kerri were thirty-five-year-old, twin sisters, they wouldn’t appreciate being spoon-fed like this.

If you wanted to convey the same information in a subtler way, you might write it like:

This makes the dialogue more about Indiana Jones than the brothers’ age, sneaking in the info so readers can figure it out for themselves.

Unrealistic smooth-talking and clichés

In your quests to craft smooth-sounding dialogue, don’t make it flow so smoothly that it sounds fake. Unfortunately, this is a weak point of sounding your dialogue out aloud because even though it may sound good, it may not sound believable. Consider reading dialogue with a friend or critique partner to see if it sounds believable coming from someone else. If it doesn’t sound any better read by your friend, it might be an indicator that your dialogue needs some work. It can also be helpful to record dialogue (with the participants’ permission, of course) and study it for natural speech patterns and phrases. (Feel free to leave out any excess “um”s and “er”s that typically accompany authentic dialogue.) Authentic-sounding written dialogue reflects real life speech.

Likewise, you should steer clear of clichés in your dialogue as much as in the rest of your writing. While it’s certainly true that people sometimes speak in clichés (though this is often tongue-in-cheek), if you find yourself writing the phrase “Are you thinking what I’m thinking?” or “Shut up and kiss me,” you may need a reality check.

For a full roster of dialogue clichés, check out this super-helpful list from Scott Myers.

Disregarding dialogue completely

Finally, the worst mistake you can make when writing dialogue is… well, not writing it in the first place! Circling back to one of the first points made in this guide, dialogue is an integral part of storytelling. It’s an important element in any story, no matter the genre because it provides exposition, indicates, personality, and character relationships, and can even be used to reveal a major plot twist during the climax.

So, what do you think of this guide? I will be adding to it periodically, so make sure to bookmark it and join my newsletter to get notifications when updates go live! Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. London: Penguin Books, 2002. Amazon.Du Preez, Priscilla. “sihouette of three people sitting on cliff under foggy weather photo.” Unsplash photo (Thumbnail photo), March 5, 2019.Leonard, Elmore. “Elmore Leonard: 10 Rules Of Writing.” Fs blog post, accessed June 27, 2021.Myers, Scott. “The Definitive List of Cliché Dialogue.” Medium article, March 8, 2012.Reedsy. “A Dialogue Writing Exercise.” Reedsy blog post, accessed June 27, 2021.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!Book Writing 101: How To Come Up With Great Book Ideas And What To Do With ThemBook Writing 101: How To Write A Book (The Basics)Book Writing 101: Starting Your Book In The Right PlaceBook Writing 101: How To Choose The Right POV For Your NovelBook Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story PacingBook Writing 101: How To Name Your Book CharactersBook Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent CharactersInfo-Dumping in Science Fiction & Fantasy Novels by Breyonna JordanHow To Write Romance: Effective & Believable Love TrianglesHow To Write Romance: Enemies-To-Lovers Romance (That’s Satisfying and Realistic)How To Write Romance: 10 Heart-Warming and Heart-Wrenching Scenes for Your Romantic ThrillerHow To Write Romance: Believable Best Friends-To-LoversHow To Write Romance: The Perfect Meet CuteCheck out my other Book Writing 101 and How To Write Romance blog posts!Check out more of my Author Advice and Writing Advice blog posts!

Recent Blog Posts

How To Write Romance: Believable Best Friends-To-Lovers

Hi writerly friends!

I’m back this week with another romance writing guide. Next week we’ll be discussing how to write believable hate-to-love romance, so I thought it’d be a great warm-up to show you guys how to writer believe best-friend-to-lovers romance. This is obviously a steppingstone and acts as the middle ground between enemies and more-than-friends in hate-to-love romance, so as you might expect, you can’t have one without the other.

However, your characters don’t always have to start out hating each other, they can indeed go from friends to lovers in a single story. Funnily for us, and embarrassingly for your characters and readers, it’s not exactly a straight shot, no—it’s a pretty rocky ride from best friends to lovers and it can be a tricky-to-write trope.

It’s unsurprising that the characters will have a bumpy time getting from one side to the other, as one is decidedly platonic and the other is decidedly romantic, and the transition from friends to lovers can be tough to read, even tougher to write, and often employs tons of awkward exchanges and cringe-worthy moments.

So, how do you write best-friends-to-lovers romance that is realistic and believable to the reader?

Step 1: Embrace The Weirdness

As you might expect, writing best-friends-to-lovers romance stories is going to feel weird, because plot twist, going from best-friends to lovers is weird! Not unearthing any best kept secrets, her—everyone knows it’s a weird shift, especially if you’ve known each other since childhood. So, when writing this trope, don’t shy away from all the weirdness, awkwardness, and embarrassing, gross feelings that happen, because it’s completely natural and these feelings should be present in the story. In fact, the reader should be able to pick up on these feeling and feel weird about it too. Secondhand embarrassment is a thing, and it’s something we want our readers turning pages to get to a point in the story when everything makes sense again and the awkwardness has died down a bit.

However, don’t go so far as to make it unrealistic. Yes, at times the uncomfortableness of the transition should be almost palpable to the reader, but keep the balance between rising and falling tension so that readers stay on the edges of their seats and grit the teeth at all the right moments.

Step 2: Determine Whether the Love is Mutual or Unrequited?

Before we get into the story structure for this trope, ask yourself whether the love between your characters or if it’s unrequited. This is very important to how the story will play out and what choices your characters will make based on their emotions, especially towards the resolution. Both routes can be delicious and heart-wrenching in their own right but know which one you’re going to go with in your own writing, will make the process a lot easier.

Jonah Hauer-King as Laurie Lawerence and Maya Hawke as Jo March in Little Women (2017) Photo by PBS.

To make it easier to chose which path your story will take, I’m going to give you a couple of examples, the first being Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, and the second being Emma by Jane Austen, (and no, I didn’t just pick these two because they involve someone being gifted a piano, but man isn’t that romantic?)

In Little Women, Laurie’s love goes unreturned when Jo tells him she never saw him as more than a friend. This sends him to Europe to avoid his heart break. When he returns after falling for Jo’s sister, being rejected again, and being inspired to do something with his life, he asks Jo to marry him. She rejects him again and ends up marrying someone else, but this story is a prime example of a best-friends-to-lovers romance that took a turn when the love was unrequited.

On the flip side, Emma, by Jane Austen Emma is startled to realize after everything, she is the one who wants to marry Mr. Knightly. When she admits her foolishness for meddling in the romances of others, he proposes, and she accepts. This is a great example of friends who become lovers where the love is returned.

Step 3: Follow The Structure

Alright, now that we got that out of the way, let’s talk about the parts of the BFTL story structure (at least that’s the acronym I’m giving it because that’s just way to much to type every time, sorry, not sorry.)

Whether or not you go by the 3-Act Story Structure, every best-friends-to-lovers romance typically follows this basic format:

Foundation

Set-up

Aha moment

Conflict

Decision

Resolution

Foundation

The first part of the structure for this trope is the foundation, where we are introduced to all core story elements, characters, setting, premise and theme. Here, the reader will get to know what exactly the story they’re reading is.

Set-up

The second part of the structure is the set-up. This is where the meet cute would occur in romance, and for best-friends-turned-lovers romance, it is no different. Introduce the characters, their relationship at this point in the story, and begin laying the groundwork for the transition from best-friends to future lovers.

Click here to read my blog post for creating the perfect meet cute.

While your story might be set preceding or following the formation of your characters friendship, it is important to know how and when they became friends, because if they become lovers later on, this will be an important part in the evolution of their relationship.

Aha Moment

This part of the story is when the characters first realize they are in love with each other. If you chose to go with the unrequited love path, then here, they would learn that one likes the other and decide they don’t feel the same way in return. Consider what path you take for this part because it will really determine how the rest of the story plays out.

Does the one who is rejected continue pursuing their friend romantically, or do they give up on the first try? Does the one who only views their friend platonically have a change of heart and end up with their friend after all? Is it a messy back and forth that never really ends with the two friends becoming lovers? Is the timing ever right? These are all important questions to ask yourself during the aha moment, because it directly drives the following course of the story.

Conflict

Remember the questions I just asked you in the aha moment section? Those questions should be asked and answered in the conflict of the story. Here we see the true feelings come out and the characters will understand the scope of the situation before them.

Decision

Saoirse Ronan as Josephine "Jo" March and Timothée Chalamet as Theodore "Laurie" Laurence (2019). Photo by Wilson Webb .

In the decision part of the best-friends-to-lovers romance, readers will see what choice the characters make based on everything they know at this point and their emotions. They might decide to get together or break up as friends, for good. Everything that has happened has led to this moment and how they react will change the course of their friendship forever. If the love is unrequited, maybe they just stay friends, but it is likely things will be weird and they’ll have to go their separate ways, like Laurie and Jo in Little Women. Perhaps they do end up getting together and marrying with a happy ending such as Emma and Mr. Knightly in Emma.

Resolution

Where do your characters go from here? How does the friendship grow or die after the decisions are made? Is there room for growth as friends and lovers or have they done irreparable damage to a good thing? Unrequited love stories are especially juicy and heart-wrenching in the resolution.

And that’s it for my guide on how to write best-friends-to-lovers romance stories that are believable and realistic. What do you think of these types of stories? Did you like Little Women and Emma? Do you prefer writing mutual or unrequited love? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below, and as always, thanks for reading!

Further reading:

—Payton

How To Write Romance: The Perfect Meet Cute

Glen Powell as Charlie Young and Zoey Deutch as Harper in Set It Up. Gif by Payton Hayes.

Hello, writerly friends!

Today, we’re discussing the meet cute. What the heck even is a meet cute anyways? Well, according to Google, is an amusing or charming first encounter between two characters that leads to the development of a romantic relationship between them.

Of course, the way you do the meet cute is completely and totally up to you—it can be cute, funny, or disastrous and comical. How you do a meet cute is completely subjective and can be created in a number of ways, but today I am going to show you how to make a meet cute even cuter—like the cutest it could possibly be.

When the reader sees the meeting coming, characters do not

While you can craft a meet cute where both the reader and characters do not see it coming, I think it’s extra interesting when the reader does, because it’s like this little secret between the writer and the reader. I really love meet cutes that do this. It’s like the sense of rising dread you get when you’re reading parts of a story with building tension—except that it’s a good kind of dread because you want the characters to end up meeting. The reader knows something good will come out of this chance encounter, only they know it’s coming, and the characters do not.

Flinn is surprised when Rapunzel hits him with a frying pan during Disney’s Tangled’s meet cute (2010).

A great example of this kind of meet cute is in Disney’s Tangled, when Flynn Rider is running from the law and seeks refuge in Rapunzel’s conveniently hidden tower. We already know Rapunzel is inside and he definitely climbed up the wrong tower. The scene that follows does not disappoint, when Rapunzel smacks him in the face with a frying pan for climbing through her window. I would consider this a comical meet cute, but it works extra well because the viewer knows what will happen before the characters and it builds for extra spicy first meeting.

Joe Bradley wakes a sleeping Princess Ann in Roman Holiday (1953).

Another example of a meet cute where the viewer/reader knows of the meeting before the characters actually meet is Roman Holiday, when Princess Ann shirks her royal responsibilities to see Rome for herself and eventually ends up falling asleep on a street. When the scene shifts to Gregory Peck playing cards with the guys, viewers just know the two are going to meet. After his night out, we see him walking down the same street Ann has fallen asleep on and we’re already anticipating their meeting.

Milo Ventimiglia as Jess Mariano and Alexis Bledel as Rory Gilmore in Gilmore Girls (2000).

Another example of a meet cute where the characters don’t know they’ll be meeting it is in Gilmore Girls, Season 2, Episode 5. Not only does this episode include Jess' first appearance, but it's also the first episode that Rory and he meet. He steals her copy of Allen Ginsberg's "Howl," only to return it to her later in the episode with notes in the margins because Ginsberg is love, you guys. Ah, Jess Mariano — you book thieving-and-annotating bad boy. When Jess swipes Howl from Rory’s room during that ill-fated dinner hosted by Lorelai, and then returns it filled with margin notes, Rory was definitely impressed. (And so were we.) This scene effectively sets up the characters before they even know each other, themselves and shows us that there’s more than meets the eye, both for the mischievous Jess and their tumultuous relationship down the line.

This kind of meet cute makes the reader feel smarter because they know something the characters don’t. This is why it feels like a special little secret between the reader and the writer because the reader feels like he or she has already figured the story out. This is especially effective if you have plot twists and turns later on in the story, because the ground work for the surprises will already be laid out for you.

Characters don’t know they’ll be seeing a lot of each other

Piggybacking on the idea that the characters don’t know they’ll end up together, another meet cute that works really well in many stories is when the characters don’t know they’ll be seeing a lot of each other and/or aren’t too thrilled about it. This is especially fun for awkward situations where the character thinks “oh well, I’ll never see them again anyways,” and then come to find out that they will be seeing them again, and a lot more at that. Awkward is cute, writers.

Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Dido Elizabeth Belle and Sam Reid as John Davinière in Belle.

Pro tip: a sense of awkwardness or secondhand embarrassment is a fantastic feeling to give the reader. It’s as strong as , if not stronger than fear or desire, because its such a vulnerable emotion and it’s one we go out of our way to avoid. If you can invoke this in your reader, then congratulations, you’ve effectively written something that makes people feel.

A great example of this type of meet cute is in the movie Belle, when Dido and John run into each other on her late-night walk. She is startled at first when she finds that he actually came bringing news for her uncle and even more so when she discovers her uncle is John’s tutor and they’ll be seeing a lot more of each other.

Another example of this type of meet cute is in Jane Eyre when Jane first meets Mr. Rochester, he doesn’t tell her who he is, but later when she returns home, she recognizes his dog and realizes the true identity of the man she’d met on the road, earlier that day.

This kind of meet cute is really great because not only does it introduce a whole new level of awkward! but it also allows us to get to know the characters before they know each other and makes their relationship down the road, a lot cuter.

Irony, or something happening that would never happen later in the story

Megan Follows as Anne Shirley and Jonathan Crombie as Gilbert Blythe in Anne of Green Gables (1985).

This is probably one of the most powerful, yet hard to pull off versions of the meet cute, but if you can nail it, it can prove for a really effective first meeting and adds dept to the relationship later. Using irony in your meet cute makes the meeting 100x better because when these two characters are in love some day and they look back on their relationship later, it will be so funny to look back and think about how ironic their first encounter really was.

One great example of the use of irony in a meet cute is in Anne of Green Gables when Anne Shirley breaks Gilbert Blythe’s slate over his head out of temper when he teases her repeatedly. This was a very effective and ironic meet cute because the two characters would never behave in such a way after they’d gotten together but it really makes for a memorable first meeting.

“I've loved you ever since that day you broke your slate over my head in school." Oh Gil❤️

The second meeting is even more awkward

Okay, the only thing better than making your reader feel the palpable awkwardness is making them feel it twice! (Or three times if you’re gutsy enough!) This kind of meet cute is incredibly effective, especially if you tie it in with the first two where 1) only the reader knows they will meet and 2) they don’t know they’ll run into each other a lot more following the first meeting. This makes for a really, really strong meet cute where the characters and the reader are almost swimming the awkward emotions and the only way to move past it is to keep reading and see how it plays out.

The first meeting happens and once it’s over and done, you can bring it back around for the second meeting which is filled to the brim with potential for even more awkwardness, shyness, embarrassment and dramatic meet cute goodness!

An example of this meet cute is in Downton Abbey when Mary Talbot and Matthew Crawley meet for the first time, she walks in on Matthew saying some offhanded things to his mother. He is talking about how he will likely be shoved into an arranged marriage with one of the Talbot daughters since their parents had heard he was a bachelor. She says she hopes she isn’t interrupting anything but of course, that proves to be the case when they meet again later and its super awkward.

Callback to the meet cute

Megan Follows as Anne Shirley and Jonathan Crombie as Gilbert Blythe in Anne of Green Gables (1985).

All of these are great ways to effectively nail the meet cute for your characters, but you get bonus points for bringing it back up later on in the story. It’s really fun to see the characters in love reflecting on their embarrassing first meeting and makes for a great treat for the reader. A callback is a really effective literary device where something happens in the beginning of the story and is later referenced towards the end of the story in another context, essentially calling it back to the reader’s memory.

Audrey Hepburn as Princess Ann and Gregory Peck as Joe Bradley in Roman Holiday (1953).

Some particularly cute examples of this callback to the meet cute is in Anne of Green Gables when Gil calls her Carrot, endearingly, in Roman Holiday when Princess Ann says “So happy, Mister Bradley,” in reference to her muttering “So happy” in her sleep on the street, and in Jane Eyre when Mr. Rochester says, “You always were a witch” to Jane in reference to their very first meeting when he’d said “Get away from me, witch!”

These are just a few really well-done meet cutes and you’ll find it’s always the little things that make these meeting iconic, memorable, and downright adorable.

That’s it for the secrets to the perfect meet cute. Try using them all and let me know what you think. Do you prefer to use one version over another or do you like using them together? Do you ever call back to your meet cutes? What is the most important element of a meet cute? And what are some of your favorite meet cutes? Let me know in the comments below!

Further reading:

Thumbnail photo by Natalie.

—Payton

Classic Romance Reading Challenge for February

A themed reading challenge for February encourages readers to explore classic romance novels, celebrating love and heartbreak through iconic literary works. Suggested titles include Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Breakfast at Tiffany's by Truman Capote, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë, and Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. Readers can follow the challenge by starting with the most romantic stories and ending with the most dramatic for a full spectrum of romantic emotions.

Hello readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by! In this shorter blog post we’re talking about classic romance reads, since it’s February and Valentine’s Day is just around the corner!

I am giving you guys a romance reading challenge for the month of February! If you’ve ever heard of Booktober, when every year during October, the bookish community participates in various spooky reading challenges to get in the Halloween holiday spirit. Instead of reading horror or thriller, we’re going to be reading romances, with a twist—we’re reading classic romances! Not only will we start the year off strong with popular classics but this list will keep our heads and hearts in the right places as Valentine’s day draws nearer. Let’s get reading!

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Jane Eyre, a young orphan under the care of her cruel, wealthy aunt attends the Lowood school where her life is less than idyllic. She studies there for years before taking a governess position at a manor called Thornfield, where she teaches a lively French girl named Adele. There, she meets a dark, impassioned man, named Mr. Rochester, with whom she finds herself secretly falling in love with. However, this classic romance transcends melodrama to portray a woman’s passionate search for a wider and richer life than that which Victorian society traditionally allowed.

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

I could go on and on for days about Austen’s Writing and she definitely has the novels to support that loving rant, but I’ll save you guys the sifting and just say that if you’re going to read Jane Austen, why not read her quintessential romance novel, Pride and Prejudice. It has all the elements of an amazing romance novel and is one of, if not the greatest romance novel of all time. It’s a witty comedy of manners that features splendidly civilized sparring between the proud Mr. Darcy and the prejudiced Elizabeth Bennet as they play out their spirited courtship in a series of eighteenth-century drawing-room intrigues.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote

An American classic that inspired one of the most influential movies of all time, Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a classic romance that opens with the unnamed narrator meeting for the first time, Holly Golightly. The two are both tenants of an apartment building on Manhattan’s upper, east side. As the story progresses, the reader learns more and more about Holly and the relationship between her and the narrator as he recounts fondly their memories and finds himself quite enamored with her curious lifestyle. She, a country girl turned New York Café Society, works as an expensive escort (not prostitute) and hopes to marry one of the wealthy men she accompanies one day.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

Another novel from the other Bronte sister, this wild, passionate romance story of the intense and almost obsessive love between Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff, a foundling adopted by Catherine’s father continues to strike readers today. The story is one of, if not perhaps the most haunting and tormented love stories ever written and tells the tale of the troubled orphan, Heathcliff and his doomed love for Catherine.

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

What list would be complete without a little Shakespeare and especially, his most famous story, Romeo and Juliet. Though anyone who has actually read it will tell you that the story doesn’t have a particularly happy ending. Romeo and Juliet is classic tale of forbidden love that showcases one of the most important questions humanity has ever faced, and that is: how far will one go for love? Elizabeth Eliot said, “There is nothing worth living for, unless it is worth dying for.” which eloquently and succinctly describes Romeo and Juliet.

Try reading these in order of most romantic to least romantic to start the month out with a really romantic read and finish it out on a little reader heartbreak. Or, read least to most romantic to end February with a happy ending.

What do you think of my February Classic Romance Reading Challenge? Have you read any of these stories before? Which of these five is your favorite and which is your least favorite? For me personally, I really enjoyed Pride and Prejudice and I look forward to rereading it this month, however I’d say Romeo and Juliet is coming in at on my list. Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

Recent Blog Posts

Written by Payton Hayes | Last Updated: March 20, 2025