How To Overcome Writer’s Block

What Is Writer’s Block?

Writer’s block is the kryptonite to a writer’s superpower—creativity. Have you ever found yourself staring at a blank page, unable to write? Perhaps you feel paralyzed by fear or unable to begin the process. Perhaps you move your hands to the keyboard, or lift your pencil to the page time and time again, only to pull them away, thinking hmm, why won’t the words just flow? Writer’s block happens to nearly every writer; it’s inevitable. Writer’s block is the inability to freely dive into writing and the feeling that whatever words come from your fingertips aren’t worth writing in the first place or won’t be good enough. The bad news? You’ve diagnosed yourself with writer’s block. But the good news? It’s treatable and an obstacle you can definitely overcome.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by! In this blog post, we’re discussing writer’s block and all it encompasses, how to overcome it, and how to keep it from interfering with your creativity. There's thousands of other posts and articles out there that explain this topic, to be sure. But I am diving deep and explaining my own personal experience with writer’s block, how I overcame it, and how you can too. This post will deconstruct the nebulous concept of writer’s block and break it down into easily understandable symptoms and actionable and effective steps for curing these symptoms. This post is a longer one, so grab your coffee, tea, and your notepad and let’s get into it!

What Is Writer’s Block?

Writer’s block is the kryptonite to a writer’s superpower—creativity. Have you ever found yourself staring at a blank page, unable to write? Perhaps you feel paralyzed by fear or unable to begin the process. Perhaps you move your hands to the keyboard, or lift your pencil to the page time and time again, only to pull them away, thinking hmm, why won’t the words just flow? Writer’s block happens to nearly every writer; it’s inevitable. Writer’s block is the inability to freely dive into writing and the feeling that whatever words come from your fingertips aren’t worth writing in the first place or won’t be good enough.

What Does Writer’s Block Look Like?

It looks like a writer hunched over their keyboard or notebook with a furrow in their brow, a purse in their lips, and a blank page before them. It looks like a lack of motivation, inspiration, or consistency. It looks like notes and binders and word documents galore, but no completed book or short story to tie them all together. It looks like an untouched laptop or notepad gathering dust in the corner. Writer’s block presents itself differently for every writer, but the symptoms are often the same. The bad news? You’ve diagnosed yourself with writer’s block. But the good news? It’s treatable and an obstacle you can definitely overcome.

What causes writer’s block?

Writer’s block, while perhaps not a proper medical condition, is a creative hurdle that stops many writers in their tracks. It stems from inexperience, underdeveloped ideas, burnout, a lack of enthusiasm, motivation, or inspiration, fear of rejection or a feeling of inadequacy when it comes to a writer’s own abilities, and maintaining a lifestyle that does not support the habit of writing. Seasoned and aspiring writers alike can suffer from this roadblock in the creative process, but with time, practice, and perseverance, writers can push past this block and eventually leave it in the dust altogether.

A woman working on a Macbook. Photo by Elisa Ventur.

Why Am I Experiencing Writer’s Block?

You may find the answer to this question below:

Inexperience: Many novice writers do not know where to begin. They don’t know how to write a story, let alone develop and format a book. They don’t know the rules of writing and that inexperience can hold them back from unleashing their creative potential. If you want to be a writer, and a successful one at that, you must educate yourself on writing tools, best practices, and storytelling as an artform. This is the foundation of being an effective and knowledgeable writer. Read books about writing, take classes and attend workshops to build your skills with practice and feedback.

Underdeveloped ideas: Many writers find themselves unable to start writing because the ideas they want to write from are not fully developed. Brainstorming and research are crucial parts of the writing process. Writing from a vague idea is much, much harder than writing from a fully-realized idea. Depending on the genre you’re writing from, take all aspects of the story and cultivate them so they can grow from a budding seed of inspiration to a blossoming concept. For example, if you’re writing a fantasy story, write detailed descriptions of all the characters, settings, world cultures, religions, and histories, timelines, and events. These wordy descriptions will likely not make it into your draft, but they will serve as notes for you to expand and refine your ideas as you write. If you can see it so clearly in your mind’s eye, then you can write from it as if you were really looking at your main characters in their world, with your own two eyes.

Lack of enthusiasm: Some writers suffer from a lack of enthusiasm about what they’re writing. This can be a difficult hurdle to overcome especially if you write for work and don’t have much of a choice in the subject matter. For those who fall into this category, you have three choices: make some kind of personal connection to the subject matter, or find a new writing job, or write for pleasure instead. For those who have an idea they really like, but feel disconnected from it or as if they don’t know enough about the topic to write on it, go back to the Inexperience bullet point. Educate yourself on the topic thoroughly enough that you can confidently and accurately write about it without feeling like you’re writing in the dark.

Lack of motivation: Many writers feel a lack of motivation when it comes to writing. This symptom of writer’s block can be one of the hardest to push past. Writers who feel unmotivated should take a realistic look at their lives and consider why they may feel that lack of motivation. Do you feel like writing at all? Do you enjoy writing? Do you enjoy storytelling and developing ideas? Do you enjoy making connections with others and sharing experiences? Do you enjoy bringing an idea to life? If any of your answers to these questions were a no, why? Why do you dislike any of these steps?

If you found yourself saying no, why are you writing —or not writing —in the first place? Why label yourself as a writer, if it's not something you actually want to do? Many writers never end up writing a book, but they don this title and put immense pressure on themselves to engage in an activity that truly doesn’t resonate with themselves. Dig deep and determine if you want to write, why you want to write, and why you are a writer. This why is your reason for doing what you do and it’s going to help you shift your mindset in a big way. If writing is your passion and purpose and being a writer is part of your identity, it will help excite and motivate you to practice writing, because it's what you do. Find your personal connection to writing and take it with you into every writing session.

Lack of inspiration: Many people who want to write a book feel as if they have nothing to write about. While a strong feeling, this idea couldn’t be farther from the truth. Every single person has a unique perspective and worldview. Every person has a unique experience. No two lives are identical and in turn, no two stories are the same. Your unique existence is valid and so is your story. If you feel like you don’t have a story or idea to write about, write from real life. Write from your experiences and memories. If you don’t want to write about your personal experiences, write fictional stories that you wish were true about your life. Go back to the Inexperience and Underdeveloped Ideas bullet points and follow those steps. Read other books from the genres you want to write from. Research topics, themes, and ideas, then develop them further into elements you can craft a story from. I like to think the writing process is like building sand castles on the beach —you have billions of grains of sand to work from, but for the castle to take shape, you must sculpt, carve, mold, chisel, and join those grains together. You must work those grains of sand until they form the shape you’re going for.

Diagnosing & Treating Writer’s Block. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

Fear of rejection: Many writers struggle with the fear of rejection whether they are aware of this or not. It comes from a combination of Inexperience, Underdeveloped Ideas, and a low self esteem as a writer. These writers may feel confidence in other areas of their lives —they may do well in school or their jobs, they may feel confidence in their physical appearances, they may be aware of other activities they excel at, but when it comes to writing, they don’t believe in themselves or their abilities. The key to overcoming this struggle is practice. Practice, practice, practice. For many writers, the process of writing is very personal and tied closely to their identity. For this reason, it can be difficult for writers to put themselves and their work out there. However, this can be one of the most freeing experiences and is vital to your growth as a writer. When I started seriously writing, I kept my fantasy stories close to my heart. I never let my friends or family read them because I didn’t want them to actually know what my writing was like, for better or worse. They knew I was a writer, but they didn’t know if I was a good or bad writer, and I clung to that uncertainty. I didn’t put my writing online or allow others to read it until much, much later, when I was in college and was somewhat forced to let others into my thoughts, emotions, and written words. From discussion posts in my online courses to writing workshops and critiques in my creative writing classes, to instructor feedback, I was required to put my writing out there, in some form or another.

What I came to realize was that I should have done this much, much sooner. I would have never broken out of my shell as a writer and a person, had I not been vulnerable and put my work out into the world for others to see, read, like, dislike, criticize, judge, compliment, and tear apart. I was terrified that someone would read my stories and think wow, this is truly poor writing. The reality is that any artform is subjective. We hear this a lot when it comes to visual art, but the same is true for writing. Subjective means “based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions” and when it comes to writing, this means readers will bring their own unique perspectives, worldviews, emotions, experiences, and opinions into the work, whether they are aware of it or not. There is nothing writers can do to stop readers from doing this, and they shouldn’t try to. As a writer, you must allow this fact of life to free you from the confines of wanting to please everyone. Allow yourself to let go of the desire to control other people’s opinions and interpretations of your work. It’s an impossibly unrealistic, unattainable, and unhealthy expectation. Whenever I find myself worrying over how others will react to my writing, I try to remember two things: Buddhism and peaches.

Let me explain.

Look, I’m not a Buddhist and I’m not telling you to convert to Buddhism. However Buddhists do practice the art of surrender. This concept is based on letting go of what one cannot control. You cannot control how others react to your writing. You cannot make them like it. You cannot please every single person with your writing, so just let this go. One of my favorite quotes is from Dita Von Teese who said, “You can be the ripest, juiciest, peach in the world, and there’s still going to be somebody who hates peaches.” There will always be someone who doesn’t like peaches and there will always be someone who can find something they don’t like about your writing. Free yourself from the desire to be liked by everyone, by being okay with rejection. Embrace it. Allow yourself to be disliked, criticized, and unaccepted. Allow yourself to produce bad writing. Allow yourself to fail. By doing this, you remove the pressure to be perfect and allow yourself to be. You allow yourself to write, no matter what comes of it. You allow yourself to grow as a writer and a person.

Writing conducive lifestyle: Many writers have a hard time writing because they do not lead a life that aligns with being a writer. To be a writer, you must have time to dedicate to reading, researching, studying, writing, editing, and honing your skills. Being a writer in practice rather than name, is more than just writing. To be a writer, you must live a life that supports the regular practice of writing and all that process entails. Writing is not only an activity, it is a lifestyle and a long-term practice. It takes years of dedication, consistency, and practice to result in expert, well-honed writing skills. If you have children or a busy life, you may find it quite difficult to carve out time to write, but it is paramount to being a good writer, let alone finding success in writing. If you answered the questions in the Lack of motivation bullet point, then by now, you should know whether or not you really want to continue writing. If the answer is no, you should probably look into something else. However, if you do, then your next objective is to set aside time every day to improve your writing. Make this a realistic and attainable goal and track your progress as you go. Start out simple and ensure your path is the one of least resistance from both yourself and others in your life.

How To Defeat Writer’s Block. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

How Do I Overcome Writer’s Block?

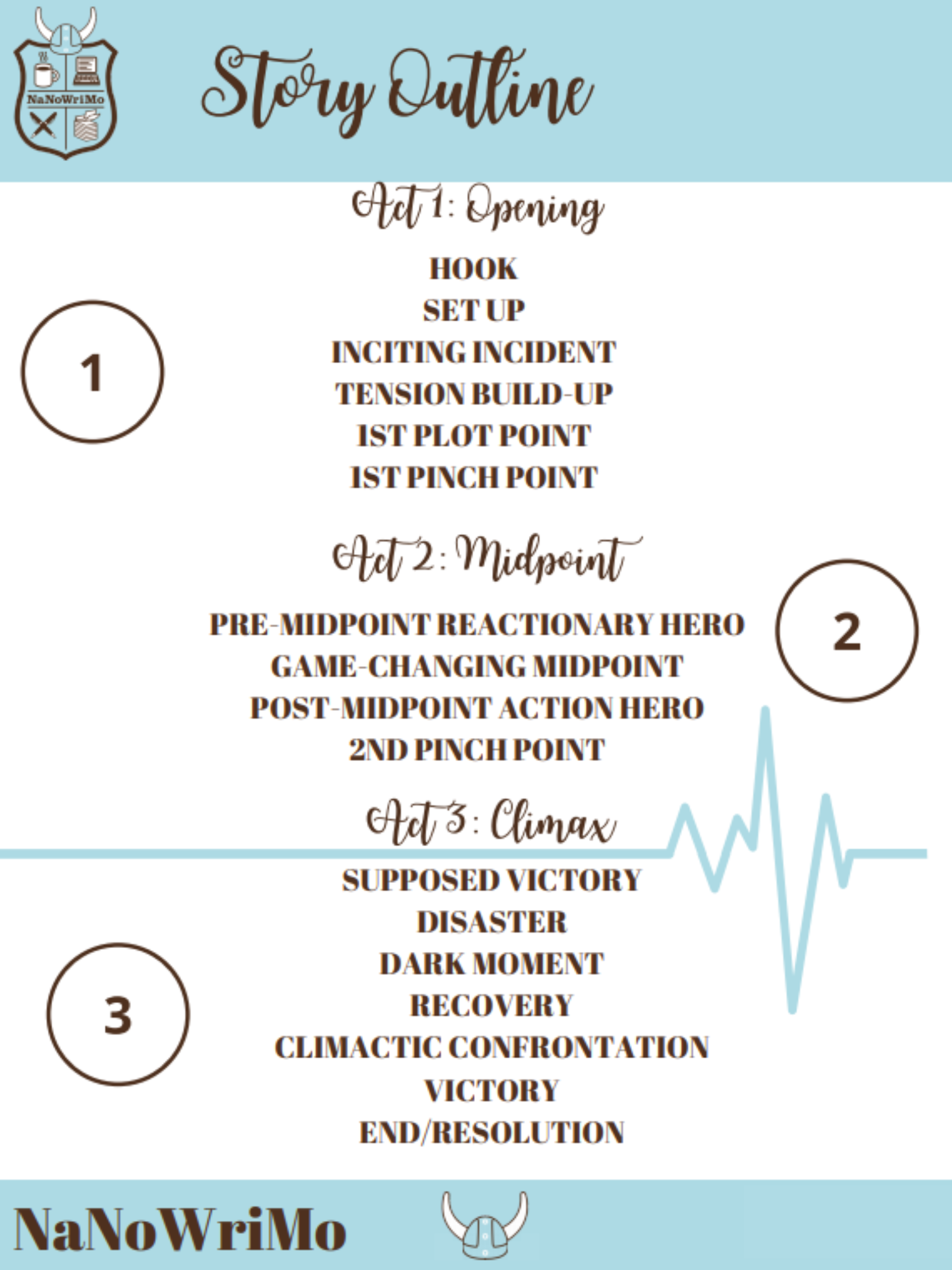

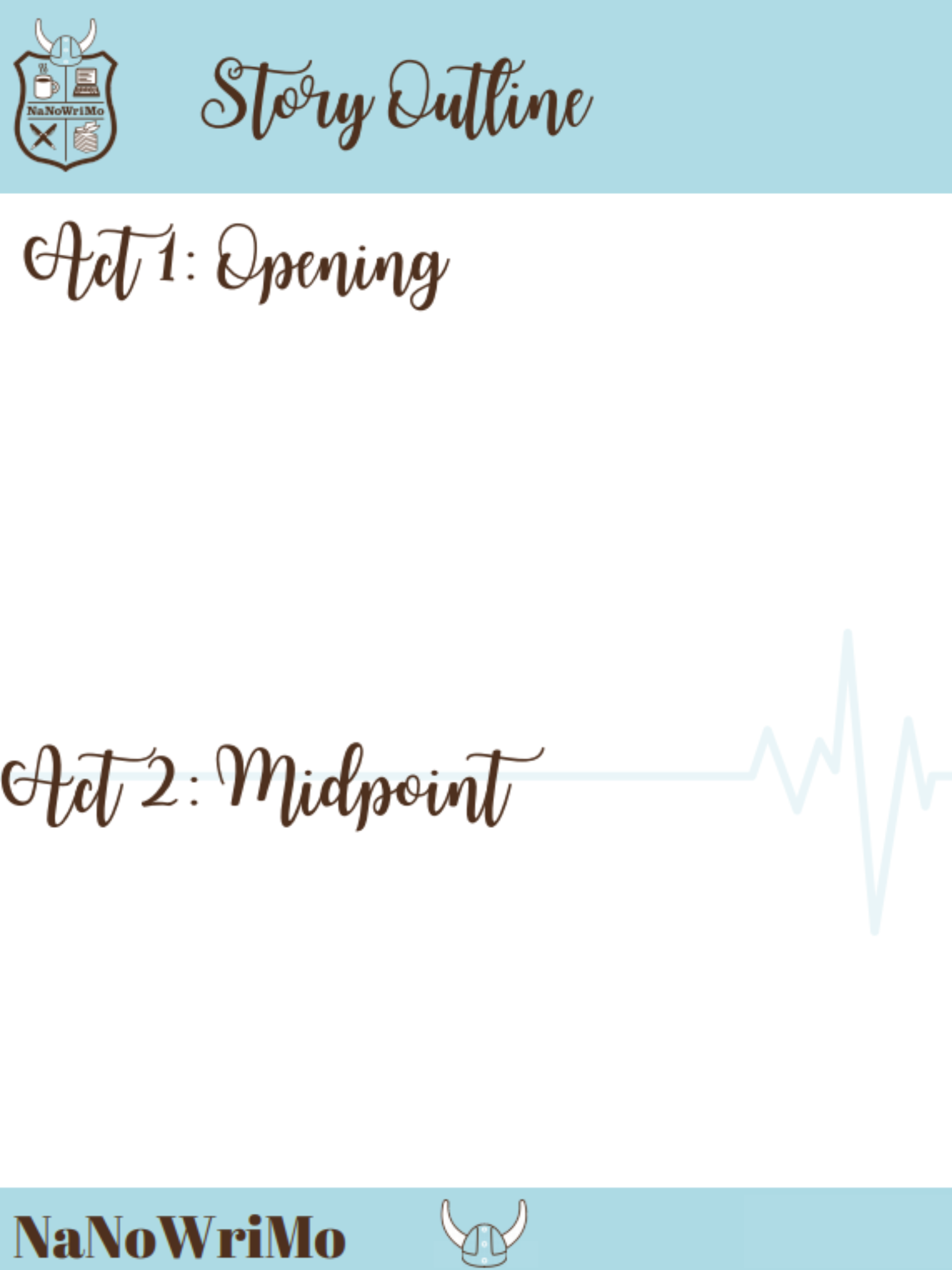

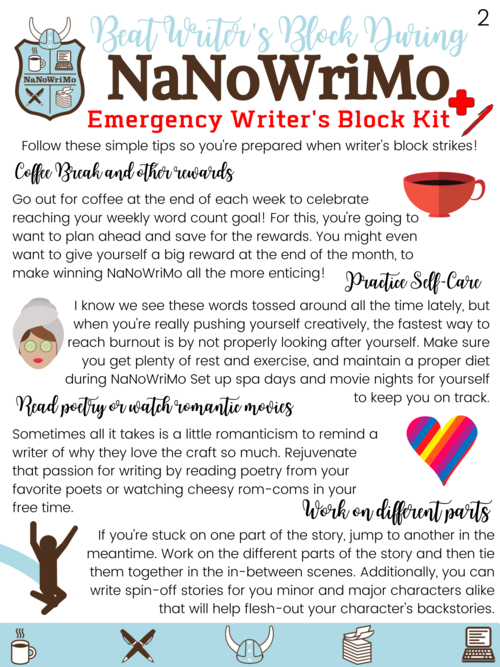

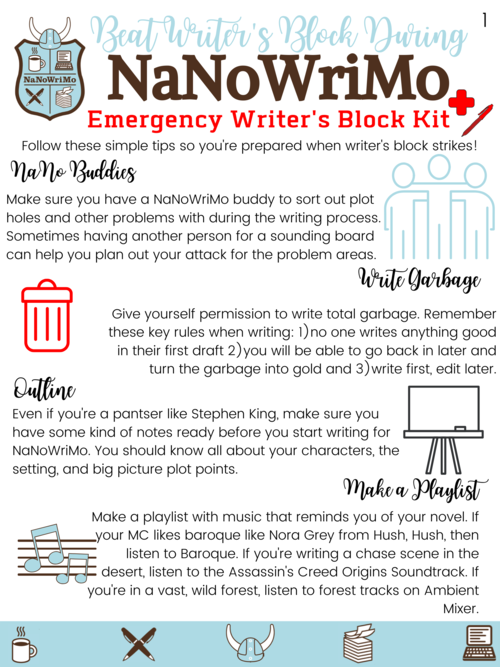

If you read through those lengthy bullet points, then by now, you know what must be done. You know what writer’s block is, what it looks like, how it affects writers, where it comes from. Now that you understand writer’s block, it is time to take action. I’ve listed several ways you can combat writer’s block. Practicing these steps will help you build the muscles you need to defeat writer's block whenever it rears its big ugly head. I have also designed a printable flier for you to put up in your writing area, so you can always have these tips equipped and at the ready when writer’s block strikes.

Writing everyday: If you are a writer, make writing a priority. The choice is up to you. If you’ve decided writing is your purpose, then make it a daily practice and make no exceptions. Tell yourself the affirmation: Writers write. I am a writer, and I am going to write. Set aside a specific time each day that you sit down and write. You will likely need more time to research, brainstorm, read, and do other writing-adjacent activities, but make sure you write every.single.day. Start with five, ten, fifteen, or thirty minutes at a time, depending on your experience and ability. If you haven’t written in months or years, set aside five minutes each day to write. Find some writing prompts or writing exercises and set a timer, then write until the timer beeps. Chances are you will feel compelled to continue writing past the time you set, but don’t force yourself to do so. If you want to spend five minutes each day working on the same writing project, you can do that too. Gradually increase your writing time as you strengthen those writing muscles and build the habit into your life. It takes twenty-one days to build a habit. That comes out to 1.75 hours across three weeks. When broken down into manageable chunks, a consistent, daily writing practice becomes more possible and over time, it becomes less like a manual task and more automatic. Five minutes every day. That’s all it takes!

Writing workspace: To make your daily writing practice easier, design a workspace that makes you want to write. Invest in a comfortable desk chair or a standing desk if necessary. Turn on soft lighting and play some instrumental music to help relax your mind while you let the creative juices flow. Make sure you have snacks and a nice warm beverage on hand. You can train your brain to get into writing mode by doing the same thing at the same time every day and employing all five senses to reinforce the habit. For example, if you want to write for ten minutes every day, starting at 7:00 p.m., start by playing your favorite song or an instrumental track you enjoy to remind yourself that it's time to write. Bonus points if you set an alarm to go off at 7:00 p.m. with the song, so it's automated and not on you to remember. While the song is playing, make yourself a cup of tea, grab a fruit or bag of chips, and get your workstation and timer ready. When you’re ready to go, start writing, and don’t stop. Remember, you’re not writing the most amazing, perfect words ever put together on earth. Just write.

Establish a rewards system that incentivizes you to write. We all enjoy different things—some of us enjoy shopping, others enjoy playing video games, and some enjoy eating delicious food. Without being counterproductive to your other goals or negatively impacting your health, come up with a rewards system that will help you reach your writing goals. If it’s your goal to write so many words each week, set a reward that will encourage and excite you to sit down to write and accomplish that goal. For example, I would like to buy a new book or two. I won’t get a new book until I finish reading one I already own, so I don’t have a bunch of unread books on my shelf. The same principle goes for writing. If you want to reach that weekly word count goal, write for the reward. You don’t have to write perfectly, just get those words onto the page.

Take care of yourself and your health: This advice is not just for writers, but because writing is so personal and tied to our mental and emotional health, self-care is an important step in creating a lifestyle that supports writing. Get plenty of quality sleep, practice good hygiene, maintain a healthy diet, and exercise regularly. For people with disabilities, mental illness, or neurodivergence, get any necessary assistance if you haven’t yet.

Some Additional Tips For Combatting Writer’s Bock

Try morning pages or a brain dump. Before you sit down to write or work on an ongoing project, try freeing your mind. The concept of “Morning Pages” comes from Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, and can be an effective strategy for getting all the mental distractions out of your way before you actually start writing. Like the name suggests, brain dump pages or morning pages are simply a page or two of everything on your mind that you want to offload so you can think clearly. It can be total nonsense, a to-do list, a stream of consciousness, a series of mad ramblings —whatever it is, get it out of your head and onto the page so you can make room for the real writing.

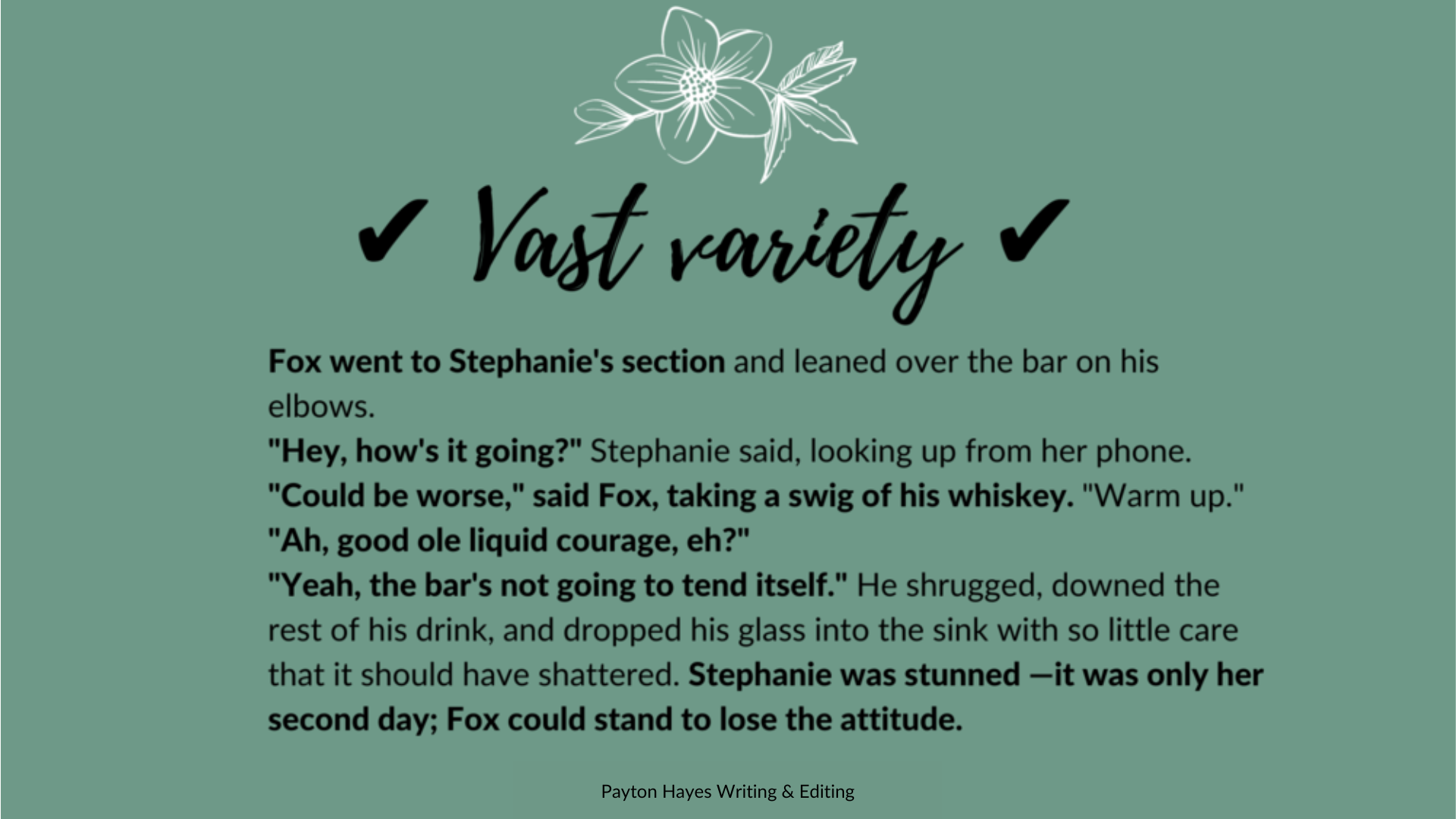

Let yourself write garbage. If you’re struggling with perfectionism and overcoming your judgmental internal editor, let yourself be okay with writing garbage. Create a new draft and title it “trash draft” if you like. Then write with reckless abandon. You can write about whatever you like or you can work on a project you’ve been writing. Make your internal editor take a backseat to your internal writer and watch as the story takes shape on the page. No writer creates perfection in the first draft, so stop telling yourself the rough draft is bad. A garbage page is better than nothing. You can create treasures from a pile of trash, but you cannot edit a blank page.

Get involved in a writing community. If external accountability is more effective for you, get connected with other writers. Network with writers, editors, publishers, and published authors for advice, craft tips, editorial news, and external motivation to keep writing. Sometimes, having a writing community can be more powerful for combating writer’s block that a routine or paycheck. Writing communities are a great way for writers to celebrate one another’s accomplishments and receive truly helpful feedback on writing.

Writer’s Block As A Result of Burnout

If you’ve made it this far, then the next piece of advice will sound quite contradictory to everything said thus far. If you’re experiencing writer’s block as a symptom of burnout, take a break. Stop writing. I know, it sounds crazy! First, I’m telling you to write, then telling you not to write. Trust me.

If you’ve done everything advised so far and nothing has worked, don’t force yourself to write when you just can’t. I’m not saying give up, but give yourself time and patience to recover from the burnout before jumping back into writing. When it is time to dive back in, do so slowly and with grace. Stick your toe in the water before diving in headfirst. If you’ve been stuck on a book for years and nothing you do can make you want to continue writing it, try writing something else. Take a break. When it’s time, you’ll come back to it. And if it’s time for you to pivot, don’t judge yourself for doing so. It may be time for a change.

Thinking Realistically About Creativity

Creativity sometimes comes from a spark of inspiration, the elusive mystical muse that chooses to strike at random. But most often, creativity is a skill you practice regularly, and it’s not as glamorous as the media makes it seem. Writing is hard work and it requires a healthy lifestyle, commitment, vulnerability, and consistency rather than artistic brilliance. Either you’ve chosen to be a writer, or writing has chosen you. If this is indeed the path you wish to take, you must go all in. I’m not telling you it’s always easy, but it does get easier with time, practice, and perseverance. When I first started out, I went years between working on chapters of the same book. Now, I write multiple blog posts each week. I still struggle with feeling motivated or excited to write. Whenever I’m dragging myself to my writing desk rather than running, go through the steps to ensure I am doing everything in my power to get myself to write. It usually works, and then once in a while it doesn’t and I know it’s time for a break. Give yourself some grace as a writer and as a human. There's a million things out there that could affect you or get in the way of your writing practice. But if you’re dedicated, determined, and willing to put in the effort, you can be a writer, and your writing will improve with every session.

You’re a writer. Writing is what you do. It’s in your bones. It is your purpose and your reason. Writing is your destiny. Now write.

Thank you for taking the time to read this blog post. I hope it helped you to better understand yourself as a writer, the struggle of writer’s block, and how to overcome it and become a better writer. If you enjoyed this post or if it helped you in some way, please leave me a comment! I’d love to know your thoughts! If you’d like to read more writing advice from me, please check out the recent posts from my blog below!

Bibliography

Ventur, Elisa. (@elisa_ventur) “a business woman who is frustrated because she is working too much.“ Unsplash photo, May 12, 2021 (Thumbnail photo).Hayes, Payton. “How To Overcome Writer’s Block.” Shayla Raquel’s Blog, February 7, 2023.Hayes, Payton. “Diagnosing & Treating Writer’s Block.” Graphic created with Canva, February 7, 2023.Hayes, Payton. “How To Defeat Writer’s Block.” Graphic created with Canva, February 7, 2023.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!When Writing Becomes Difficult5 Reasons Most Writers QuitSelf-Care Tips for Bookworms5 Healthy Habits For Every WriterYoga For Writers: A 30-Minute Routine To Do Between Writing Sessions8 Reasons Why Having A Creative Community MattersThe Importance of Befriending Your CompetitionKnow The Rules So Well That You Can Break The Rules EffectivelyBlank Pages Versus Bad Pages: How To Beat Writer’s BlockWriting Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & DisciplineLet’s Talk Amateur Author Anxiety: 7 Writer Worries That Could Be Holding You BackWhy Fanfiction is Great Writing Practice and How It Can Teach Writers to Write WellScreenwriting for Novelists: How Different Mediums Can Improve Your WritingExperimentation Is Essential For Creators’ Growth (In Both Art and Writing)20 Things Writers Can Learn From DreamersCheck out my other Writing Advice blog posts!

Recent Blog Posts

How To Submit Your Writing To—And Get It Published In—Literary Journals

To successfully publish your work in literary journals, it's essential to understand the submission process and tailor your approach accordingly. Begin by thoroughly researching potential journals to ensure your work aligns with their editorial focus and submission guidelines. Resources like Poets & Writers' Literary Journals and Magazines Guide offer valuable insights into various publications. Before submitting, meticulously revise your work to ensure it meets the highest standards. Adhering to each journal's specific submission guidelines is crucial. Keep in mind that many journals claim first North American serial rights, meaning they seek to be the first to publish your work. By carefully selecting appropriate journals, refining your work, and adhering to submission protocols, you increase the likelihood of seeing your writing published in esteemed literary outlets.

With 2023 wrapping up and the new year just around the corner, I thought it would be helpful to share some amazing resources for writers looking to submit their work in 2024! Many literary journals are still accepting submissions into 2024 and there are plenty of publications looking for high-quality writing for their next issue! Below is an in-depth guide for submitting your writing as well as a list of my top Oklahoma-based literary journals that I’d recommend submitting to!

A photo of several literary journals and an antique typewriter on my home bookshelf. Photo by Payton Hayes.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If this is your first time visiting my blog, thanks for stopping by, and if you’re a returning reader, thanks for coming back! Although I have been occupied with external commitments, I aim to increase my posting frequency in 2024.

You’re going to want to get your bookmark button ready because there’s a ton of useful links in this post! 🔖

If you’re reading this blog post, you’re probably a creative or literary writer looking to share your work with the world! Whether you’re a seasoned author or debut writer, literary journals (also called literary magazines) are a great way to get your work out there! Literary journals are periodicals that are committed to publishing the work of writers at all stages of their careers. Most literary journals publish poetry, prose, flash fiction, and essays, but many of them publish photography, paintings, and other visual art as well!

With 2023 wrapping up and the new year just around the corner, I thought it would be helpful to share some amazing resources for writers looking to submit their work in 2024! Many literary journals are still accepting submissions into 2024 and there are plenty of publications looking for high-quality writing for their next issue! Below is an in-depth guide for submitting your writing as well as a list of my top Oklahoma-based literary journals that I’d recommend submitting to!

Know Your Market

First off, do your research! The next couple of points go hand-in-hand with this idea, but to ensure the best possible chance at success with your submissions, it is crucial to conduct thorough market and publisher research rather than submitting blindly. According to Poets & Writers, “Your publishing success rests on one axiom: Know your market.”

I recommend starting with Poets & Writers’ wonderfully thorough guide to Literary Journals and Magazines where you can find details about the specific kind of writing each magazine publishes and in which formats, as well as editorial policies, submission guidelines, general expectations, and contact information. They also have an amazing database of nearly one thousand literary magazines and journals, as well as a helpful submissions tracker so you can easily keep track of which journals you’ve submitted to, how many times you’ve submitted a poem, story, or essay; the amount of money you’ve spent on fees; the status of your submissions; and how much time has passed since you submitted your work all in one place online.

Poets & Writers’ Literary Journals and Magazines Guide (🔖Bookmark this!)

Poets & Writers’ Literary Journals and Magazines Database (🔖Bookmark this!)

Most writers get the attention of editors, agents, and other writers by first publishing their writing in literary magazines or literary journals. (Many literary magazines and journals will offer you a modest payment for the writing they accept, sometimes by giving you a free copy, or contributor’s copy, of the issue in which your work appears.) Before beginning the submission process, it is essential to research the market to determine which publications are the best venues for your writing. Your publishing success rests on one axiom: Know your market.

—Poets & Writers

Some other useful resources courtesy of Poets & Writers include:

Poets & Writers’ List of Open Reading Periods: Journals and Presses Ready to Read Your Work Now (🔖Bookmark this!)

CLMP ‘s Directory of Publishers (🔖Bookmark this!)

New Pages’s Literary Magazines Guide (🔖Bookmark this!)

Heavy Feather Review’s Where To Submit List (🔖Bookmark this!)

Duotrope - An amazing paid resource with SO many useful features from a publishing database with over 7,500 active publishers and agents, news pages, publishing statistics and reports, a submission tracker, theme and deadline calendar, and interviews from editors and agents that can provide insight into specific publications.

Along with the aforementioned guides and resources from Poets & Writers, I also recommend Writer’s Market, Poet’s Market, and Novel & Short Story Writer’s Market, all published by Writer’s Digest Books, and give detailed contact information and submission guidelines.

Submission Guidelines and Questions To Consider

When researching your literary magazine presses, be sure to keep in mind the following questions:

What kind of work is being published?

How often do they publish?

What are their submission guidelines?

Do they allow simultaneous submissions?

Do they require previously unpublished works?

In what ways does this publisher “pay” contributors for their work—cash reward or free copies of the finished publication?

Does this journal offer awards to high-quality submissions?

Can you purchase additional copies or is there a limit per contributor?

Where and how does this journal accept submissions?

What is the contact information for this publisher in the event that you need to withdraw your submission?

What experiences have other contributors had with working with this magazine? Is the communication clear and open?

What is the turnaround time for approval and rejection letters?

Does this journal offer alternative publishing options such as online exclusives or in weekly newsletters?

These are just a few questions to keep in mind when submitting your work to literary journals. I personally try to keep a variety of large and small journals, and those that accept submissions year-round (rolling submissions) or multiple times throughout the year, on my calendar.

Literary Market Place (Book-mart Press) has larger publisher and literary agent listings, and The International Directory of Little Magazines & Small Presses (Dustbooks) is a print directory you can find on sites like Amazon. You can also utilize their online database.

Find The Right Publisher For You and Your Work

Not all publishers are created equal and not all books are “big five” books. What I mean by this is that not every book—or piece of writing—will get published by one of the big five publishers and not every book is going to be on one of The New York Times’ bestsellers lists. But this isn’t inherently a bad thing. Some books are best suited for bigger publishers while others are best suited for smaller publishers and publishing your work with the right press is critical for success in the publishing industry. The same is true for literary magazines. Not every work is suited for The New Yorker or Poetry Magazine.

There are many pros and cons to publishers of all sizes, but the primary difference is that big publishers often have more resources and a wider audience reach, but they are often far more selective when it comes to which books they publish. On the other hand, smaller publishers may not have the clout that big publishers do but they often are more intimate and personal when it comes to submissions, communications, and the publishing process. Additionally, big publishers usually have bigger marketing budgets, while small publishers often allow greater creative control when it comes to decision-making in the publishing process. Alternatively, there are medium-sized publishers that tend to have the best of both worlds and fall somewhere in between. If you’d like to read more about the pros and cons of publishing houses of all sizes, check out this fantastic article from Publishers Agents Films.

That being said, I think you should absolutely shoot for the stars when submitting and querying. I can’t help but think of the Wayne Gretzky quote, “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

A screencap of Michael Scott from The Office, courtesy of NBC and Katherine Arnold.

And Gretsky is 100% correct. However, when it comes to the publishing industry, success doesn’t happen by accident or luck alone. Writers must be selective and strategic in their submission process, just like publishers. It is important to be realistic about what kind of publishers will be the best for your work—it’s just a matter of good fit.

Below are some great articles about working with small versus large presses.

“Small Press Vs Big Press: What Is The Difference?” by Winnifred Tataw of Win’s Books Blog

“The New York Times Bestseller List.” by Seth Godin of Seth’s Blog

“The Big Five US Trade Book Publishers.” by Ali of The Critical Thinker

“Big Six Publishing is Dead–Welcome the Massive Three.” by Kristen Lamb

Publisher Tiering and Simultaneous Submissions

Once you understand the benefits and drawbacks of small, medium, and large presses, one way to prepare for submissions is by tiering prospective publishers. I first learned about this process from Clifford Garstang, author of Oliver’s Travels and other novels, and editor of the acclaimed anthology series, Everywhere Stories: Short Fiction from a Small Planet.

Tiering is an aid to simultaneous submissions that groups the best magazines together in the top tier, somewhat less prestigious magazines in the next tier, and so on. It is advisable to submit work to the top tier first, or at any rate within the same tier, so that an acceptance by one, which requires withdrawal from the others, won’t be painful. (If you get an acceptance from a lower-tier magazine while you’re still waiting to hear from a higher-tier magazine, that could lead to a difficult withdrawal. Withdrawal is ethically required, but what if the higher-tier magazine was about to accept the piece?) So, I decided to rank literary magazines—first in fiction, because that’s what I was writing, but later in poetry and nonfiction because many people requested that—to help me decide where to submit. In theory, I would aim toward the top of the list and work my way down until someone finally accepted my story.

—Clifford Garstang

Garstang meticulously prepared a wonderfully helpful ranking chart for 2023 Literary Magazine Rankings. I have no doubt these rankings will look quite similar, next year as well, but until we have an updated list, I’ll be going by his 2023 list.

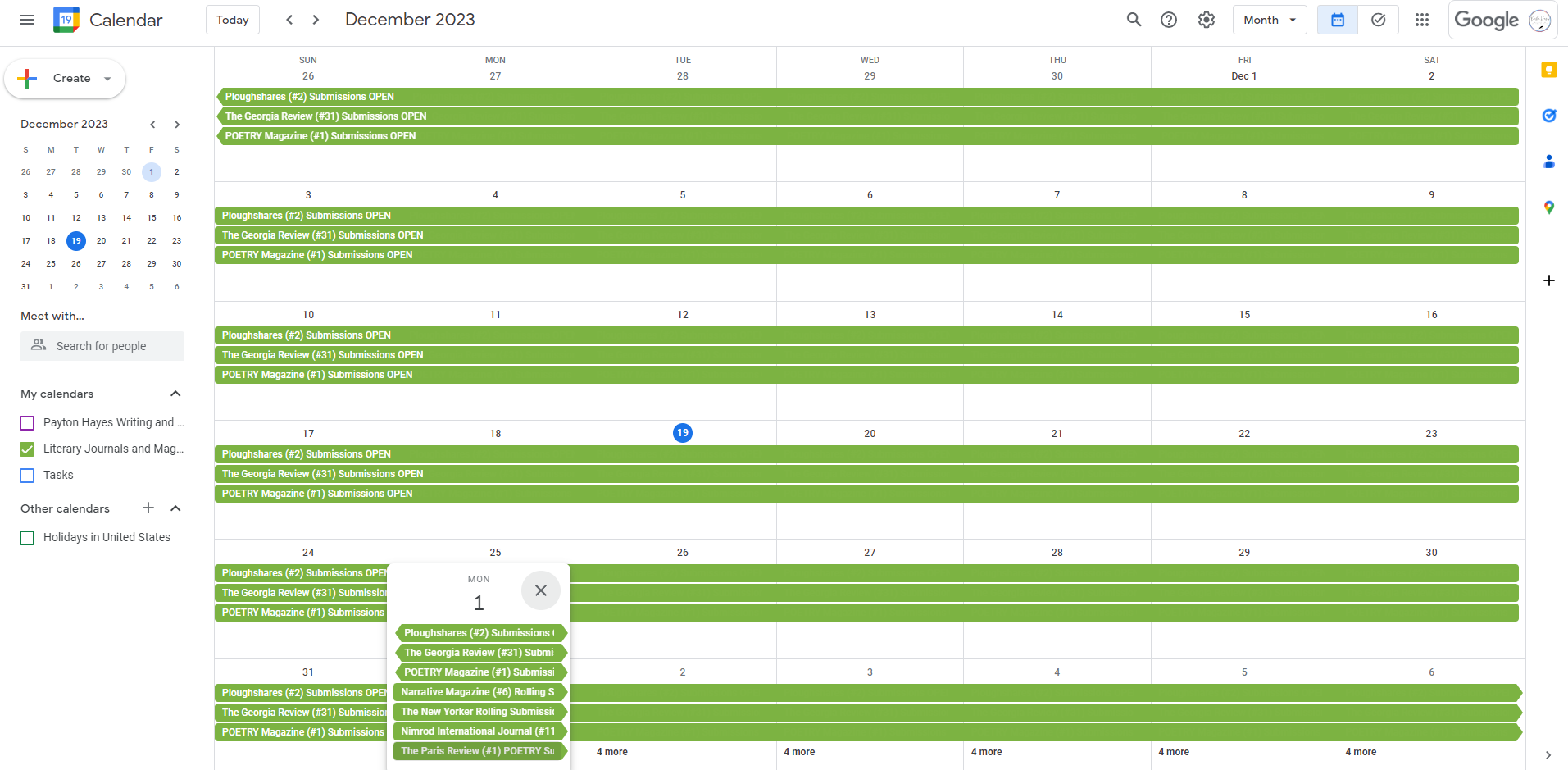

Track Submission Deadlines With Calendar Blocking

Another great way to prepare for submitting your work in 2024, is to block out submission windows for all the presses you’re interested in submitting to. I typically keep my favorite fifteen literary journals' submission windows in my Google Calendar and a master list of many other potential magazines' submission windows, organized by date, in a Google doc. That way, I keep the top fifteen literary journals I’d like to publish with at the forefront of my mind and I can easily find other publishers throughout the year. I’d recommend researching literary magazines at all levels in your desired category—poetry, prose, essays, and visual art and making your own master list that is tailored to your work. Making a specific list based on your work will prove far more useful to you than simply going by my list.

Pro Tip: You can either block out submission openings AND closings or just the openings. In the image below, you can see that I usually just block out the opening dates and assume any blocks of time without that event means they’ve closed.

A screencap of Submission Calendar Blocking in Google Calendar. Photo by Payton Hayes

A photo of Nimrod International Journal Fall 2023 issue, Awards 45 on a wooden side table. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Maintain A Consistent Submission Schedule and Make Time For Your Writing Rituals

In addition to tracking submission deadlines, it is also a good practice to make and keep a consistent submission schedule for yourself. Once you’ve got a couple of pieces that you feel confident in publishing (and have been edited and proofread), start sending out a couple of submissions each week. I also suggest creating some sort of rejection ritual. You will inevitably face rejections, but instead of letting them get you down, let them be part of the process. Whenever you receive a rejection letter, print it out and burn it or tape it to your writing desk as motivation to keep writing and keep submitting. Likewise, come up with some kind of acceptance ritual—some way to celebrate each of your accepted submissions. No matter the amount of rejections you receive, don’t get discouraged! It just takes time and perseverance. The more you submit, the easier the whole process will get, I promise.

Besides, sometimes even if you don’t get accepted, you still get a freebie out of it in the end and who doesn’t like free stuff? I submitted to Nimrod International Journal in 2023 and while none of my submissions were accepted, they still sent me a free copy of the issue I submitted to. If I’m honest, I wasn’t expecting them to send me a free copy—they send one free copy out to all contributors, but since I was rejected, I didn’t think I counted as a contributor—and it sort of felt like a tiny slap in the face. But after some time passed, I realized it wasn’t personal and was grateful to have the free copy.

Oklahoma Literary Journals

As a writer and editor based in Oklahoma, I’m pretty familiar with the literary scene here in the scissortail state and I’d like to take a moment to share a few of my favorite literary journals that I’ve personally had the pleasure of working with.

New Plains Review—January 15 for the Fall 2024 issue and July 15 for the Spring 2025 issue

New Plains Review, a student-run literary journal at the University of Central Oklahoma, proudly receives hundreds of submissions from all over the world. Keeping with the University of Central Oklahoma’s goals of both excellence and diversity, it is our mission to share with our readers thought-provoking, quality work from a diverse number of authors and artists around the world. We are eager to help these creators broaden their audience and reinforce the importance of the arts in our everyday lives.

1890: A Journal of Undergraduate Research—September 15

The purpose of 1890: A Journal of Undergraduate Research is to provide undergraduate students the opportunity to demonstrate their interests and abilities in various disciplines by accepting works of research, creative writing, poetry, reviews, and art. New Plains Student Publishing uses 1890 to encourage, recognize, and reward intellectual and creative activity beyond the classroom by providing a forum that builds a cohesive academic community.

The Central Dissent: A Journal of Gender and Sexuality—Opening summer of 2024

The Central Dissent: A Journal of Gender and Sexuality is an interdisciplinary academic journal produced by New Plains Student Publishing and sponsored by the UCO's Women’s Research Center as well as the LGBTQ+ Student Center. Being the first and only academic journal focused on gender and sexuality in Oklahoma, our mission is to gather and disseminate quality research, poetry, and academic reviews that explore gender theory, gender identity, as well as how race, class, and ethnicity shape society’s expectations of the individual both currently and historically.

Pegasus—Opening in early 2024

Pegasus is the annual literary journal of original art, poetry, photography, personal essay, and fiction by Rose State College students, faculty, and staff. 2024 Submission deadline to be announced.

Nimrod International Journal of Poetry and Prose—January 1 to October 1 for general submissions in prose and poetry and January 1 to April 1 for the Nimrod Literary Awards contest

Nimrod International Journal welcomes submissions of poetry, short fiction, and creative nonfiction. We publish two issues annually. Our spring issue is thematic, with the theme announced the preceding fall. Previous themes have included Writers of Age; Range of Light: The Americas; Australia; Who We Are; Islands of the Sea and of the Mind; The Arabic Nations; Mexico/USA; and Crossing Borders. The fall issue features the winners and finalists of our annual Literary Awards. In most cases, both issues also contain work accepted as general submissions throughout the year.

Literary Magazines currently accepting submissions into 2024

Erin Duchesne of Make A Living Writing has compiled a fantastic list of 18 Literary Magazines Accepting Submissions in 2024 so I figured I’d include a condensed version of it here as well as a link back to the article for your convenience.

Literary journals with submissions open year-round:

Asimov’s Science Fiction —Rolling Submissions

Harper’s Magazine —Rolling Submissions

Narrative Magazine —Rolling Submissions

The Sun Magazine—Rolling Submissions'

The New Yorker—Rolling Submissions

Literary journals with one submission deadline:

Ploughshares—June 1 to January 15

POETRY Magazine—September 16 to June 14

The Sewanee Review—September 1 to May 31

The Georgia Review—August 16 to May 14

The Kenyon Review—September 1 to 30

Literary journals with multiple submission deadlines:

AGNI —September 1 to December 15; February 14 to May 31

The Iowa Review—August 1 to October 1 for fiction and poetry; August 1 to November 1 for non-fiction

The Gettysburg Review—September 1 to May 31; graphics accepted year-round

New England Review—September 1 to November 1; March 1 to May 1

Swamp Pink—September 1 to December 31; February 1 to May 31; prize submissions are accepted in January

The Paris Review—March and September for prose; January, April, July and October for poetry

Granta—March 1 to 31; June 1 to 30; September 1 to 30; December 1 to 31

Literary journals with submissions opening soon:

One Story—Opening in early 2024

Although this list is a great place to start for literary journals that are currently still accepting submissions going into 2024, I still highly recommend you research your market and put together a tailored list for journals you plan to submit to in the coming year. And that’s it for my guide to all things literary journals and magazines! This is by far not a comprehensive list, but I tried to be as thorough as possible! What did you think of this guide? Let me know in the comments below! If you know of any amazing resources not listed here, please leave me a comment to and I’ll get them added to this post! Thanks for reading and supporting my work!

Bibliography

Arnold, Katherine and NBC. “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take – Wayne Gretzky – Michael Scott” – The Campus Activities Board.” Lanthorn Website, November 25, 2019. (Wayne Gretzky quote/Michael Scott meme from NBC.)Duchesne, Erin. “18 Literary Magazines Accepting Submissions in 2024.” Make A Living Writing, accessed December 18, 2023.Garstang, Clifford. “2023 Literary Magazine Rankings: Overview.” Clifford Garstang.com, December 19, 2023.Gus. “The Pros & Cons of Working With a Small or Large Publisher.” Publishers Agents Films Website, October 30, 2014.Hayes, Payton. “A photo of Nimrod International Journal Fall 2023 issue, Awards 45 on a wooden side table.” December 18, 2023.Hayes, Payton. “A screencap of Submission Calendar Blocking in Google Calendar.“ December 18, 2023.Hayes, Payton. “A photo of several literary journals and an antique typewriter on my home bookshelf.” December 18, 2023.Hayes, Payton. “Oklahoma literary journals on a wooden bookshelf.” March 14, 2024 (Thumbnail photo).Poets & Writers staff. “Literary Journals & Magazines.” Poets & Writers website, accessed December 18, 2023.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!Self Care Tips for BookwormsHow To Overcome Writer’s BlockWhen Writing Becomes Difficult5 Reasons Most Writers QuitSelf-Care Tips for Bookworms5 Healthy Habits For Every WriterYoga For Writers: A 30-Minute Routine To Do Between Writing SessionsThe Importance of Befriending Your Competition8 Reasons Why Having A Creative Community MattersBlank Pages Versus Bad Pages: How To Beat Writer’s BlockKnow The Rules So Well That You Can Break The Rules EffectivelyLet’s Talk Amateur Author Anxiety: 7 Writer Worries That Could Be Holding You BackWriting Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & DisciplineBook Marketing 101: Everything Writers Need To Know About Literary Agents and Querying8 Ways To Level Up Your Workspace And Elevate Your ProductivityGet Things Done With The Pomodoro TechniqueHow To Organize Your Digital Life: 5 Tips For Staying Organized as a Writer or FreelancerCheck out my other Freelancing, Writing Advice, and How To Get Published blog posts!

Recent Blog Posts

How To Write Poems With Artificial Intelligence (Using Google's Verse by Verse)

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been integrated into various creative fields, including poetry. Google's experimental tool, Verse by Verse, assists users in composing poems by offering suggestions inspired by classic American poets. To use the tool, individuals select up to three poets from a list that includes Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Edgar Allan Poe. After choosing the desired poetic structure—such as quatrain, couplet, or free verse—and specifying parameters such as syllable count and rhyme scheme, users input the first line of their poem. The AI then generates subsequent lines, emulating the style of the selected poets. It's important to note that while AI can provide creative suggestions, human intervention remains crucial in refining and finalizing the poem, ensuring authenticity and personal expression.

This blog post was written by a human.*Please note that exclusively using AI to write and publish text-based content is unethical and should not be done under any circumstance. In this post, I demonstrate how to utilize AI as a tool for writing practice, but I do not condone the use of AI to produce text without extensive editing and human intervention. In fact, I highly advise against it. In absolutely no cases should AI-written content be submitted to editors, agents, or publishers, nor should it be published online or in print materials. AI should never be used to replace the art of writing and storytelling through text. This is just a fun, light-hearted post that shows how writers can experiment with AI to help get their creativity flowing, much like warming up with writing exercises. Please keep in mind that AI use poses various ethical and environmental ramifications. I strongly encourage you to do your own research before trying out the techniques in this blog post for yourself. Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by, and if you’re a returning reader, it’s nice to see you again! In this post we’re going to explore writing poetry using artificial intelligence (AI). I heard about this from an article a few years ago. I tried to find it, but so many others have come out discussing the same topic since then and it seems it’s been buried in the search results. However, I have linked some particularly interesting articles at the end of this post for further reading. All other articles quoted in this post will be linked at the end as well.

Artificial Intelligence

Before we can create poetry using artificial intelligence, we must first understand what the term means in definition as well as what it means for the future of humanity. Artificial intelligence is changing the world in ways no one can yet fully predict.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) of Oxford University Press defines artificial intelligence as:

“Noun. The capacity of computers or other machines to exhibit or simulate intelligent behaviour; the field of study concerned with this. Abbreviated AI.” (OED 2008)

Artificial intelligence can also be described as the theory and development of computer systems that are able to perform tasks such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, translation between languages, and other tasks that normally require human intelligence. Initially, AI included search engines, recommendation algorithms such as those used by YouTube, Amazon, and Netflix, computer programs that could play games like chess with users. In the last decade, we have seen an emergence of AI applications that can complete a myriad of tasks that typically require human intelligence. These applications include understanding and responding to human speech (apps such as Siri and Alexa), self-driving cars (such as Tesla), and even art making and poetry writing programs (such as the infamous Lensa app and Verse by Verse by Google).

In his article, “Can AI Write Authentic Poetry?” cognitive psychologist and poet Keith Holyoak explores whether artificial intelligence could ever achieve poetic authenticity. In the article, he makes the comparison of AI to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein:

“On the hazier side of the present horizon, there may come a tipping point at which AI surpasses the general intelligence of humans. (In various specific domains, notably mathematical calculation, the intersection point was passed decades ago.) Many people anticipate this technological moment, dubbed the Singularity, as a kind of Second Coming—though whether of a savior or of Yeats’s rough beast is less clear. Perhaps by constructing an artificial human, computer scientists will finally realize Mary Shelley’s vision.” (Holyoak 2022, par.6)

Despite the bleak predictions of how AI may one day replace all human activity, the reality is that this technology is simply not there yet. While AI can simulate human intelligence successfully in many tasks, it is still lacking in the poetry writing department and requires humans to be the editors and final decision makers in the outcome of a poem. Holyoak explains this current iteration of poetry AI being a system that “operates using a generate-then-select method” (Holyoak 2022, par.10).

In his article, Keith Holyoak ponders the validity of AI poetry, functionalism, the Hard Problem of consciousness, and the critical essence or subjective experience within poetry. I have linked his article at the end of this blog post, and I highly encourage you to read it if you’re even remotely interested in these topics.

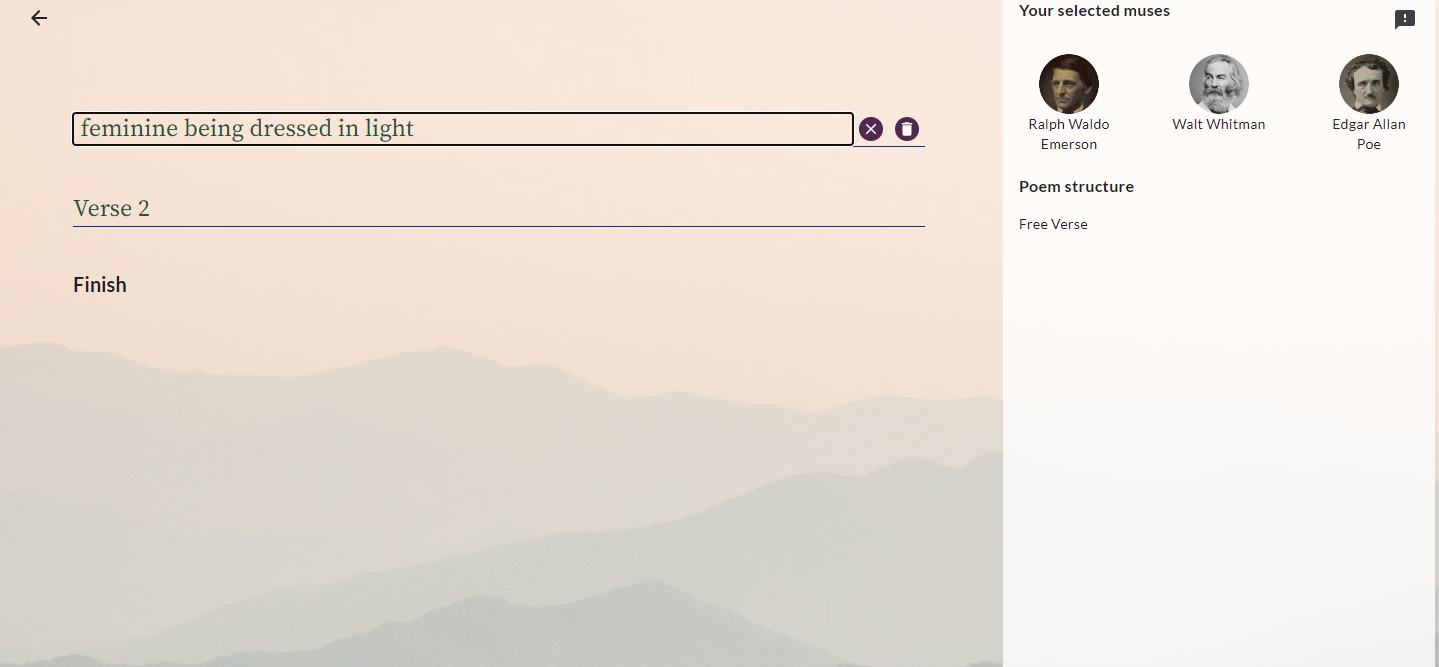

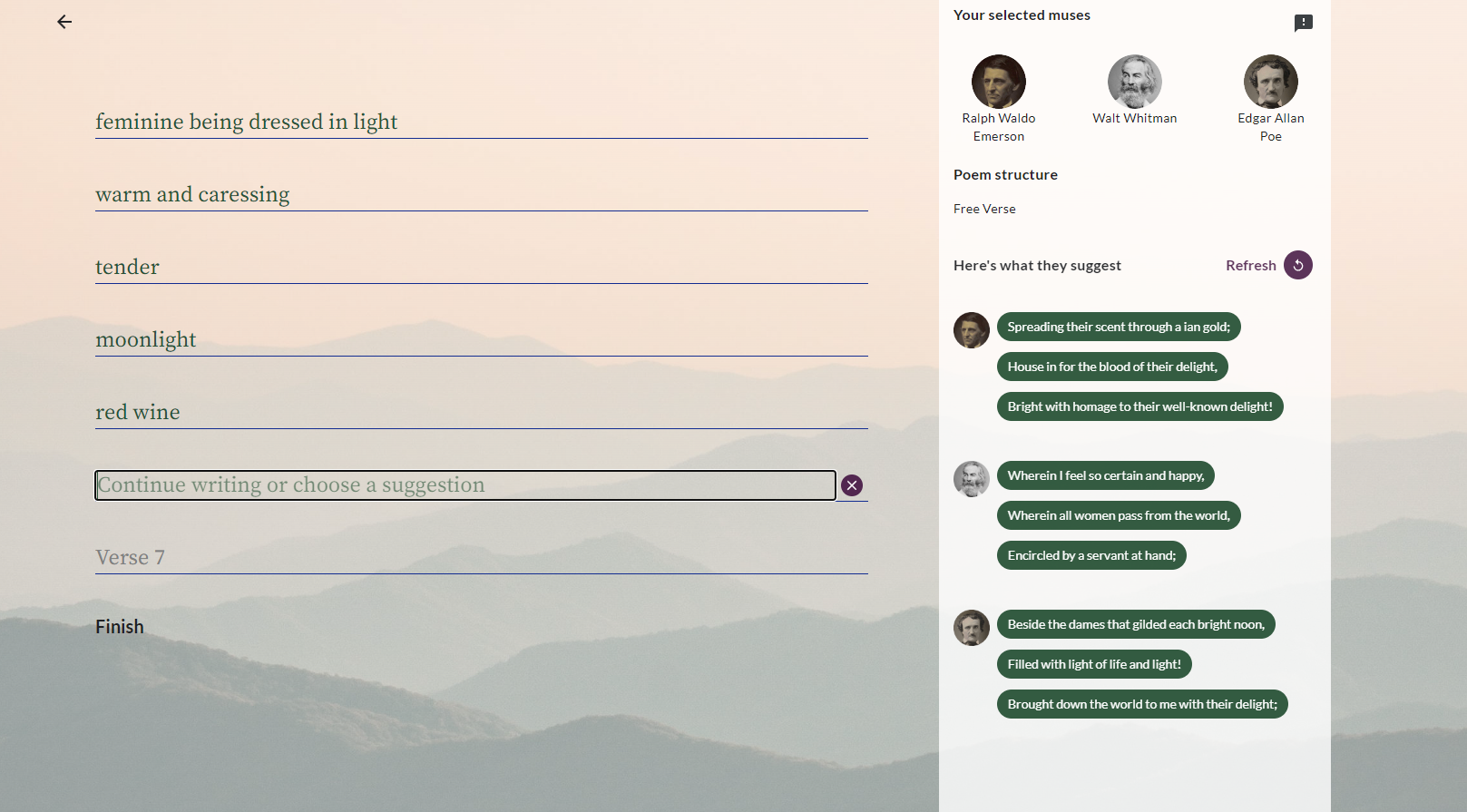

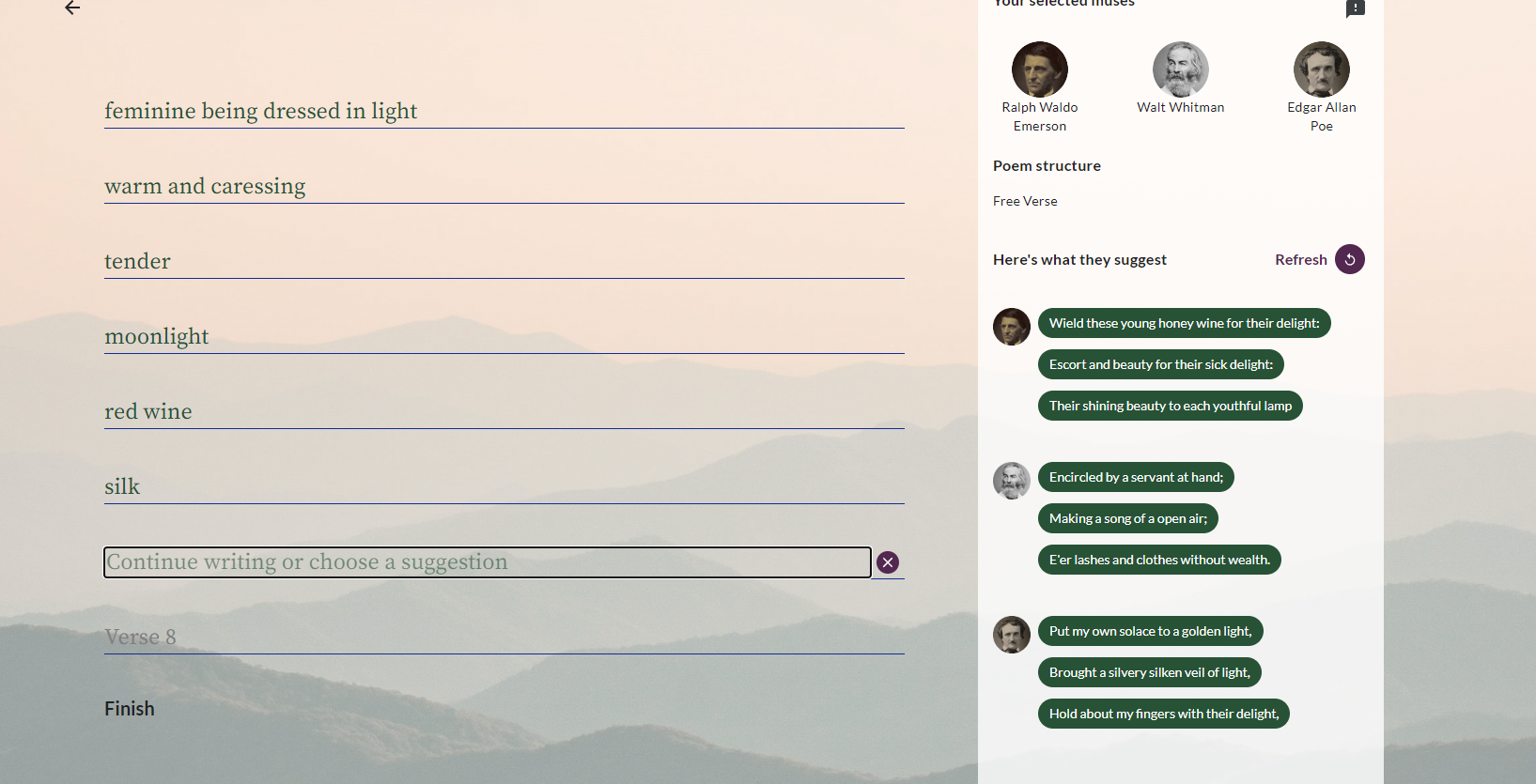

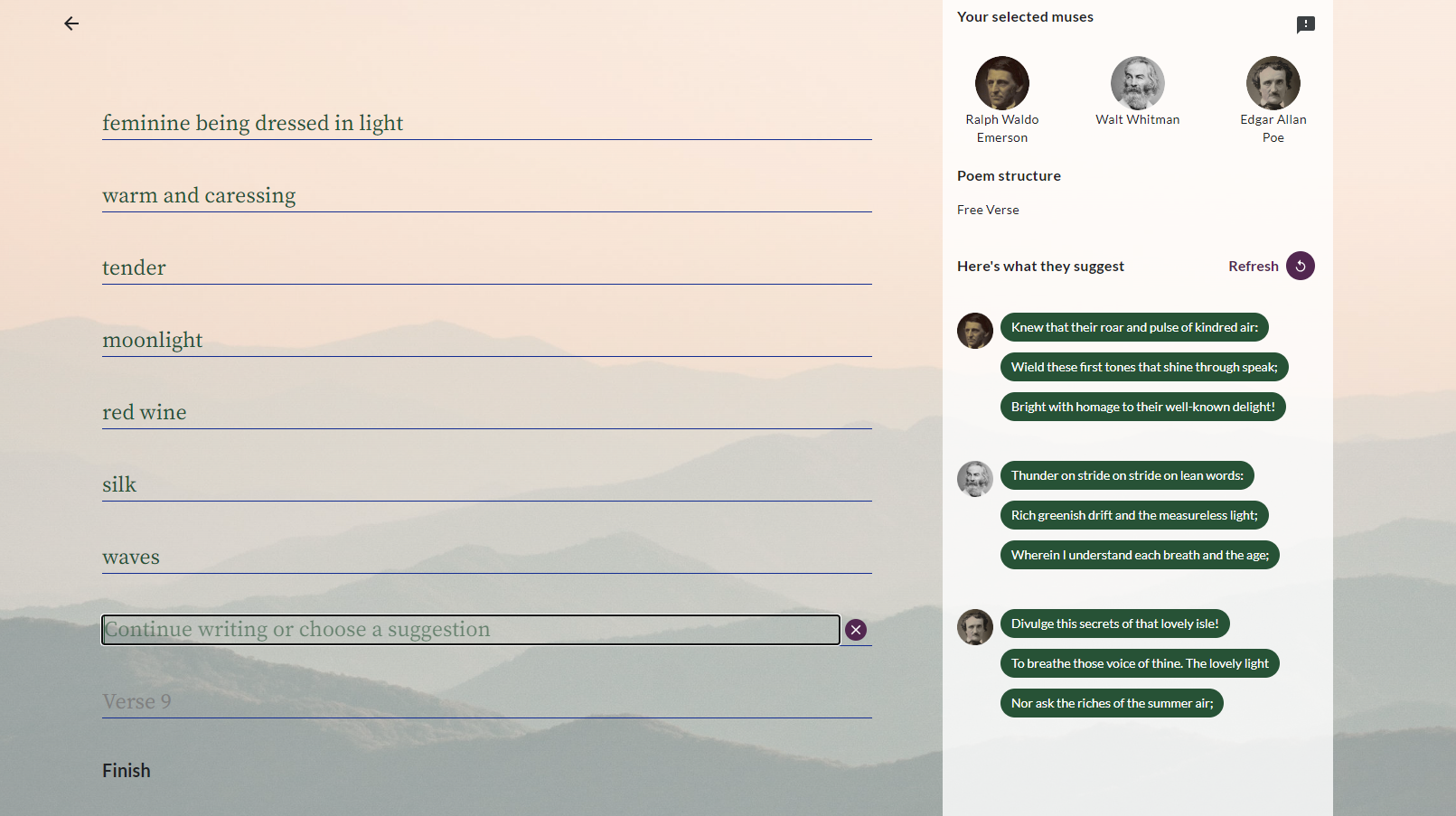

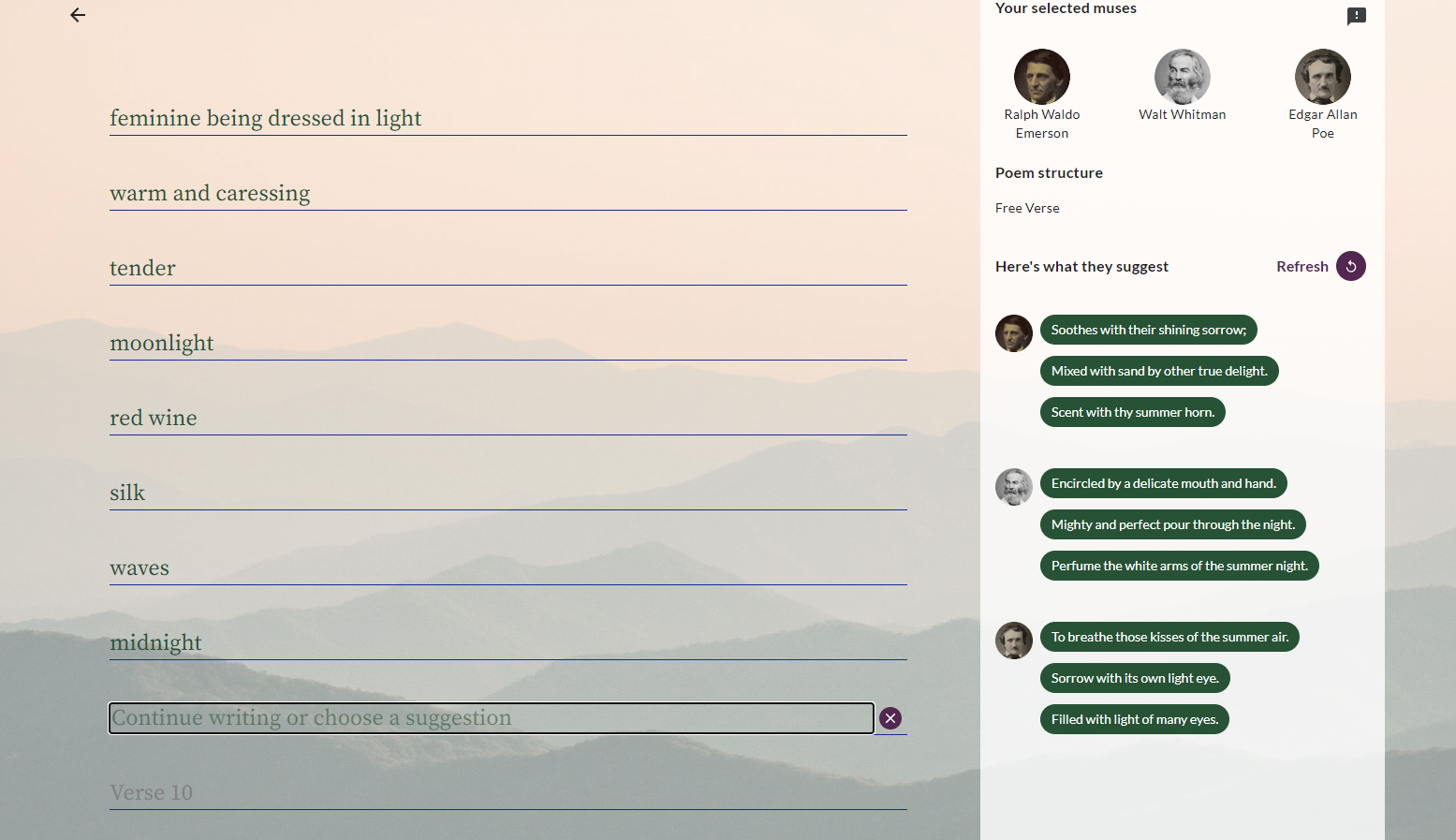

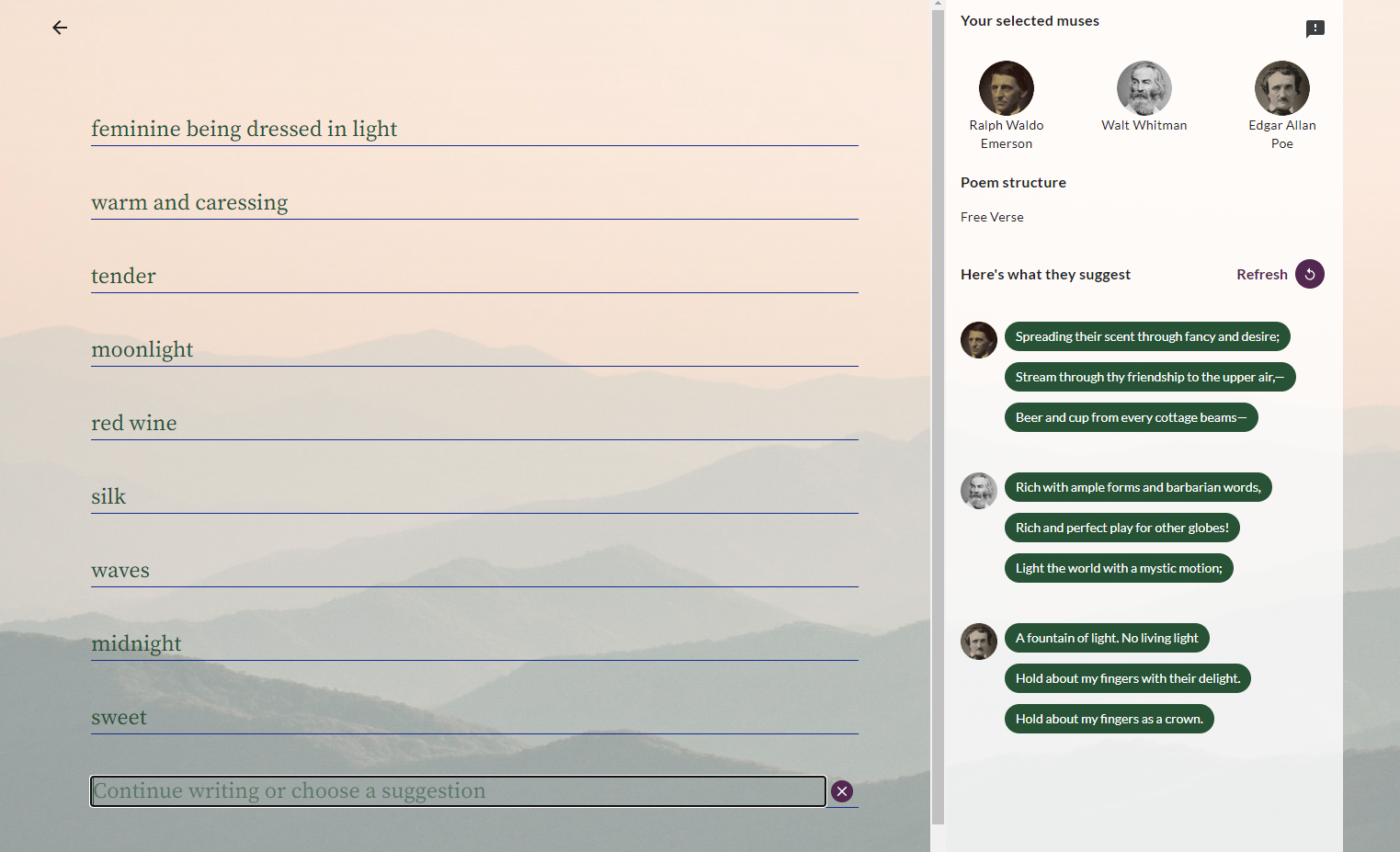

Users can select up to three poets to serve as their muses. They will provide suggestions as you write. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Google’s Verse by Verse

Verse by Verse is a powerful poetry-writing AI created by Google that produces suggestions line by line, inspired by famed classical poets such as Emily Dickinson, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. The tool allows users to select up to three poets they want to mimic from a list of twenty-two classical poets.

Google’s about section on the Verse by Verse demo page says this of the software:

“Verse by Verse is an experiment in human-AI collaboration for writing poetry. We have created a cadre of AI poets, trained on the poems of many of America's classical poets, to work alongside you in writing poetry.

Each poet will try to offer suggestions that they think would best continue a poem in the style of that given poet. As such, try working with different poets to see whose style best meshes with your own.

Explore what works best for you when composing the poem. You can try using the poets' suggestions (including editing them to better match your style!), or write your own inspired by what they suggest.” (Google)

I conducted a little more research to gain a better understanding of how the AI operates and how best to use it for writing my own poetry. The article “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ can help you write poetry” by Aditya Saroha provides insight into how the muses provides suggestions based on classical poets. Saroha said, “Google explained that Verse by Verse's suggestions are not the original lines of verse the poets had written, but novel verses generated to sound like lines of verse the poets could have written. To build the tool, Google’s engineers trained models on a large collection of classic poetry. They fine-tuned the models on each individual poet’s body of work to try to capture their style of writing” (Saroha 2021, par.8-10). So, the poetry that the tool’s muses provide the user with were not actually lines crafted by classical poets, but rather inspired by their individual bodies of work.

In the article, “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ Lets You Imitate Writing Style Of Your Favourite Classical Poet” by Rudrani Gupta, provided quotes from one of Google’s software engineers, Dave Uthus where he explained how the AI was trained to write like classical poets. She said, “The suggestions of the new verses are possible because the tool has been ‘trained to have a general semantic understanding of what lines of the verse would best follow a previous line of verse,’ said engineer Dave Uthus. ‘Even if you write on topics not commonly seen in classic poetry, the system will try its best to make suggestions that are relevant,’ he added” (Gupta 2020, par.4). By training the AI in this fashion, the tool allows modern poets to write about modern topics, themes, and concepts, while imitating classical style and voice.

While this software can prove to be a useful writing too, it isn’t intended to replace talented poets. Saroha concludes his article by noting that the tool is meant to aid poets rather than replacing them. He said, “Through the tool, Google aims to ‘augment’ the creative process of composing a poem. Google said Verse by Verse is a creative helper, an inspiration and not a replacement” (Saroha 2021, par.11 ).

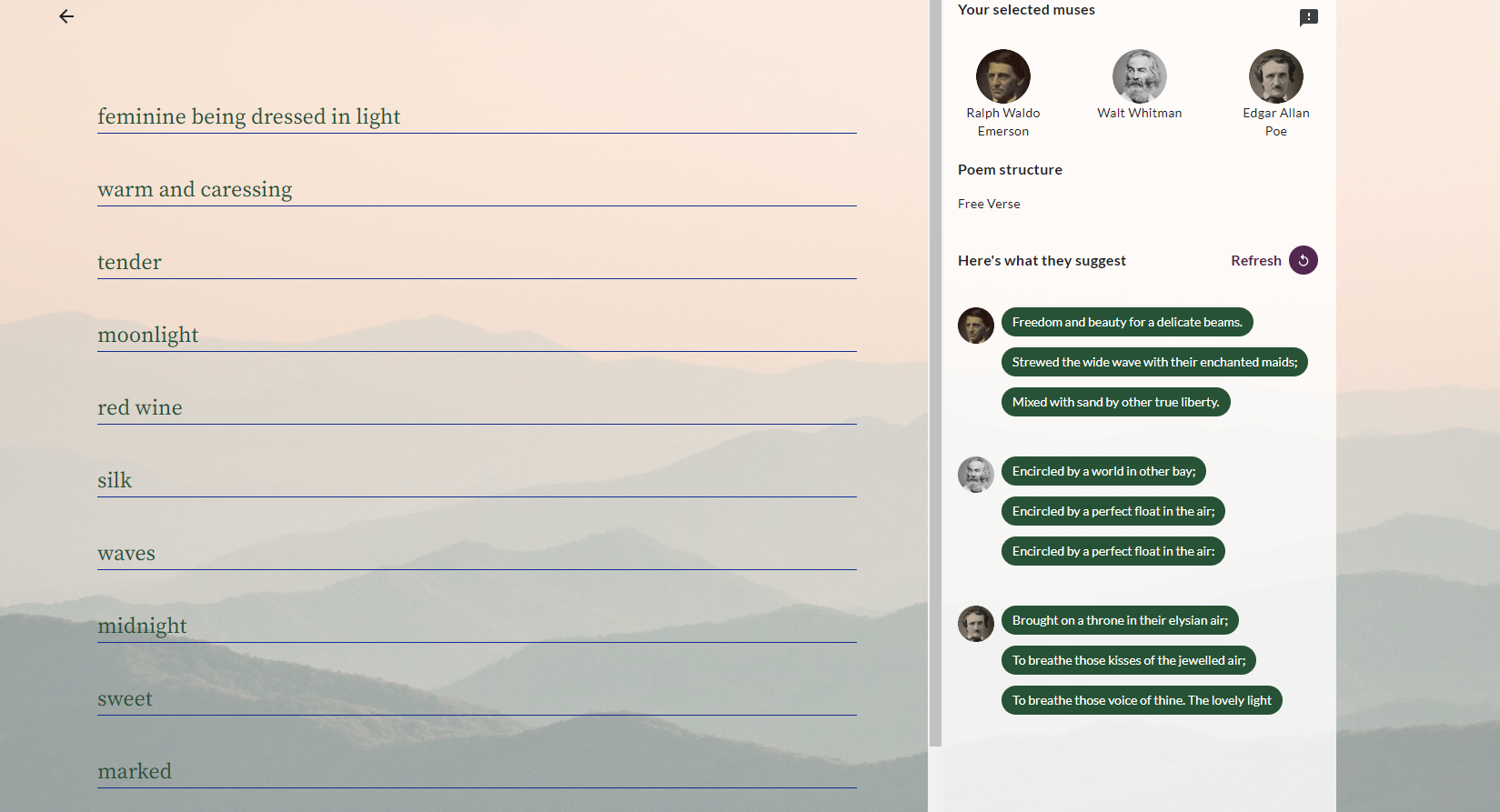

Google’s Verse by Verse, an AI poetry-writing tool. Photo by Payton Hayes.

I First Used Verse by Verse In 2020

I was first introduced to Verse by Verse in 2020 and I tried it just to see how effective it could be. At the time, I was really getting into my own religious deconstruction and exploring overt sexuality and expression. As a result, my writing at the time certainly reflected my interests and spiritual journey. I typed in words such as holy, prayer, pleasure, love, lust, sex, worship, devotion, god, and church. The poets I selected as my muses were Whitman, Emerson, and Poe and as I wrote each verse on the left, they provided me with inspiration from the column on the right.

I do not have the original poem the AI created when I first did this exercise in 2020 however, from that, I ended up with the following poem:

PRAYER

"Oh God," she says, hands clasped together, fingers entwined, knees bent.

He doesn't answer; he does.

he answers with earnest, continued, devoted worship

head bowed, eyes closed, his mind devoid of all else but this

—this soul-shaking, earth-shattering pleasure, this blessed communion between man and woman,

the Holy Spirit an undoubted voyeur through the candlelight,

this holy practice wherein they do some of their finest praying. (Hayes 2020)

Revisiting Verse by Verse in 2022

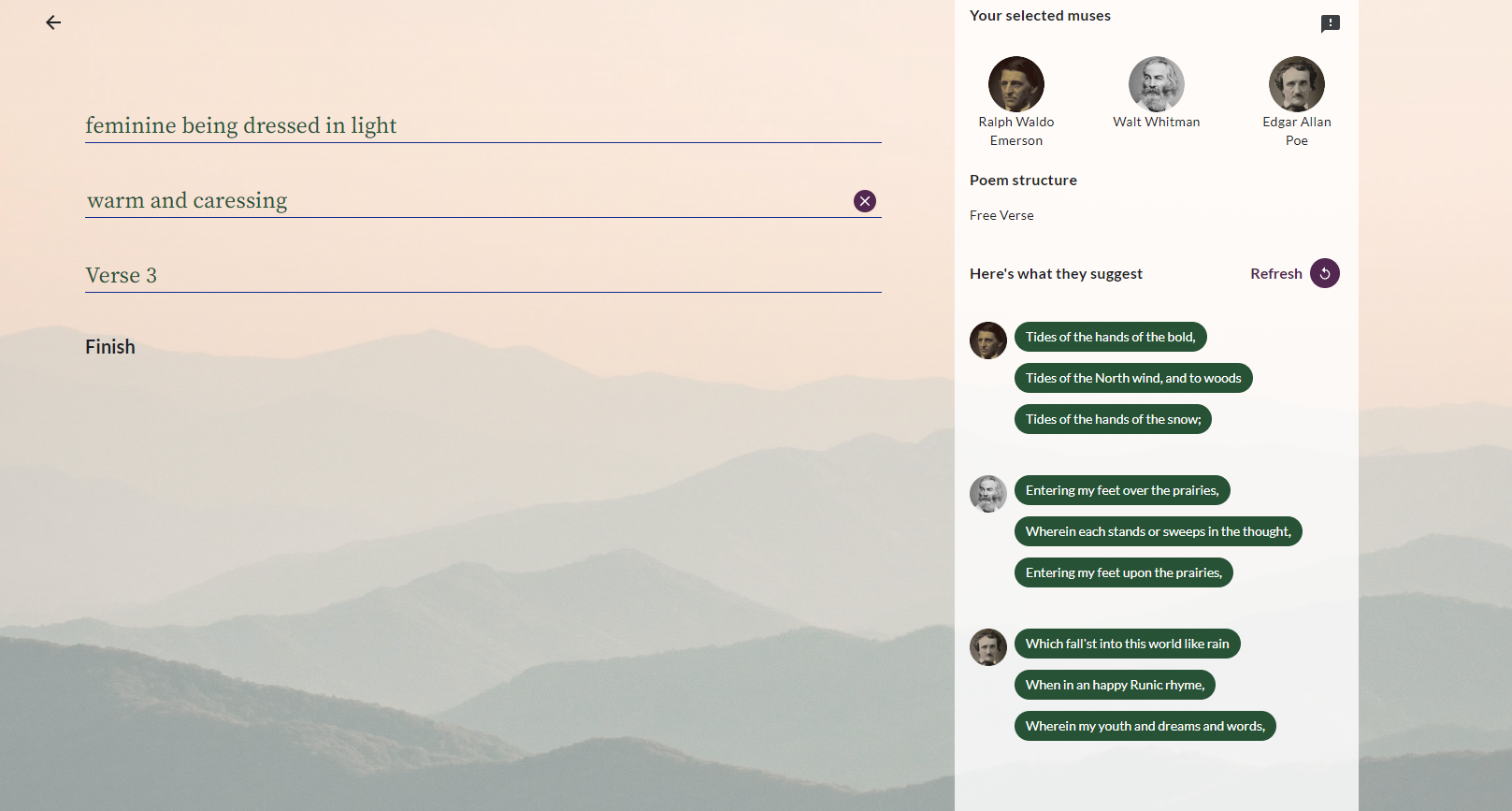

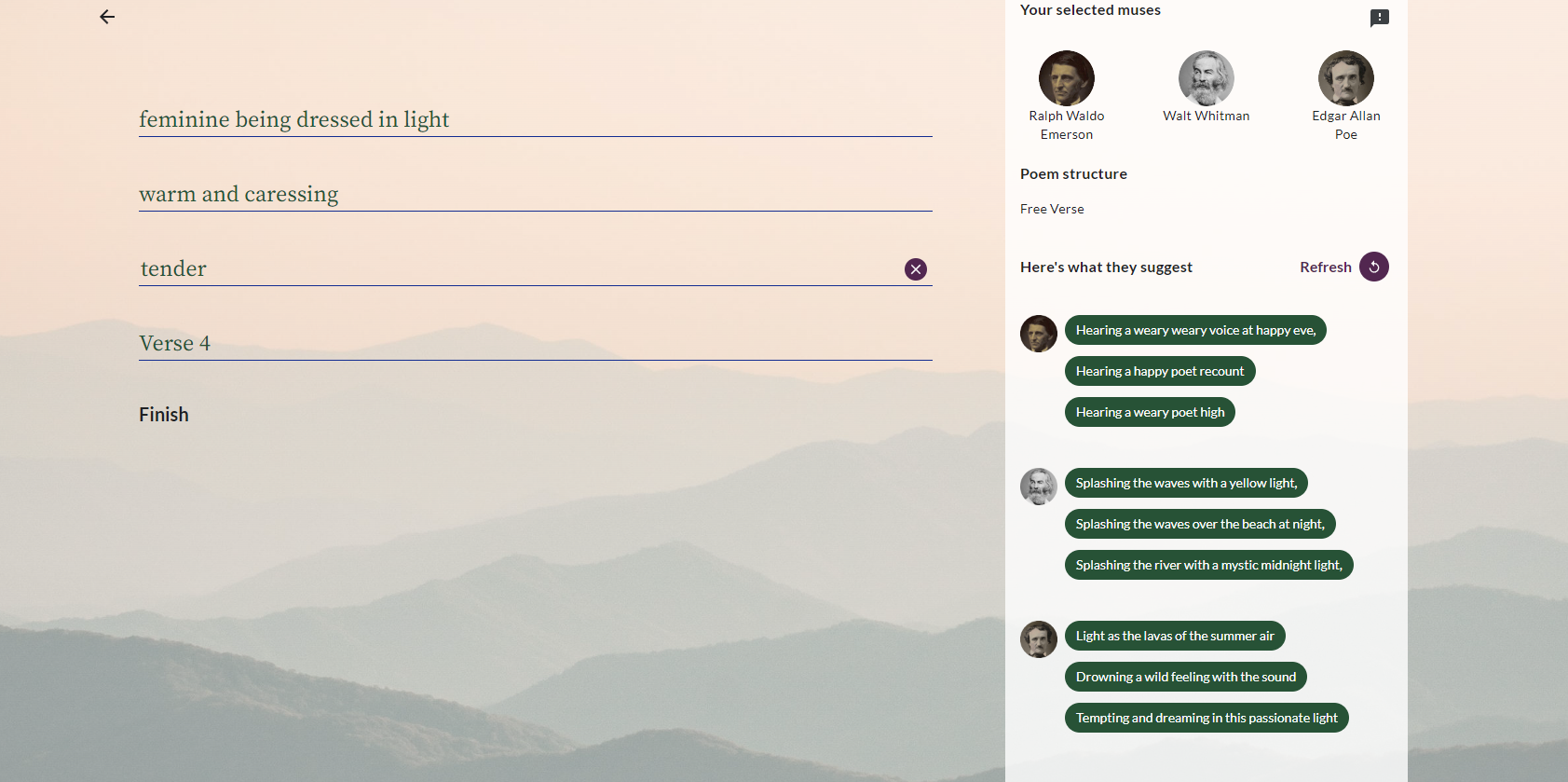

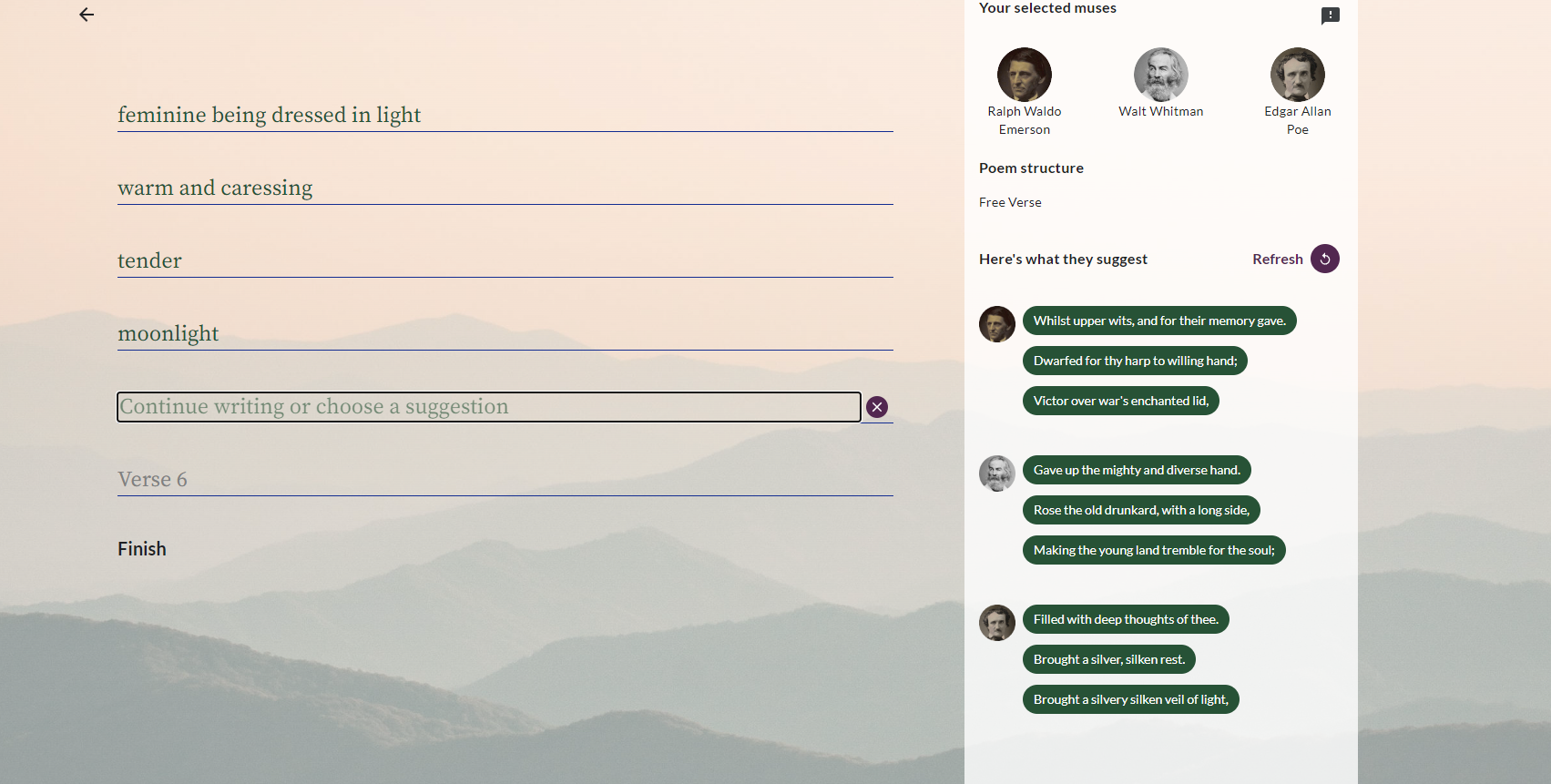

To show you how this AI writes poetry and how it’s suggestions can be effective for your own poetry writing, I decided to give it another go in 2022. Below is a gallery of screenshots from the tool as I entered each verse/line at a time. As you can see, my muses Emerson, Poe, and Whitman all provided me with interesting and unique suggestions to include in my poem.

I used words and phrases that came to mind, without rhyme or reason. I typed out ten verses and my chosen muses produced three lines each to help inspire my poem. Below are the twenty-seven lines from each poet in the right column (totaling eighty-one lines among my muses).

Ralph Waldo Emerson Muse

Tides of the hands of the bold,

Tides of the North wind, and to woods

Tides of the hands of the snow;

Hearing a weary weary voice at happy eve,

Hearing a happy poet recount

Hearing a weary poet high

Whilst upper wits, and for their memory ave

Dwarfed for thy harp to willing hand;

Victor over war’s enchanted lid

Spreading their scent through a ian gold;

House in for the blood of their delight,

Bright with homage to their well-known delight!

Wield these young honey wine for their delight:

Escort and beauty for their sick delight:

Their shining beauty to each youthful lamp

Knew that their roar and pulse of kindred air:

Wield these first tones that shine through speak;

Bright with homage to their well-known delight!

Soothes with their shining sorrow;

Mixed with sand by other true delight.

Scent with thy summer horn.

Spreading their scent through fancy and desire;

Stream through thy friendship to the upper air,--

Beer and cup from every cottage beams–

Freedom and beauty for a delicate beams.

Strewed the wide wave with their enchanted maids;

Mixed with sand by other true liberty.

Walt Whitman Muse

Entering my feet over the prairies,

Wherein each stands or sweeps in the though,

Entering my feet upon the prairies

Splashing the waves with a yellow light,

Splashing the waves over the beach at night,

Splashing the river with a mystic midnight light,

Gave up the mighty and diverse hand

Rose the old drunkard, with a long side,

Making the young land tremble for the soul;

Wherein I feel so certain and happy,

Wherein all women pass from the world,

Encircled by a servant at hand;

Encircled by a servant at hand;

Making a song of a open air;

E’er lashes and clothes without wealth.

Thunder on stride on stride on lean words:

Rich greenish drift and the measureless light;

Wherein I understand each breath and the age;

Encircled by a delicate mouth and hand.

Mighty and perfect pour through the night.

Perfume the white arms of the summer night

Rich with ample forms and barbarian words,

Rich and perfect play for other globes!

Light the world with a mystic motion;

Encircled by a world in other bay;

Encircled by a perfect float in the air;

Encircled by a perfect float in the air:

Edgar Allan Poe Muse

Which fall’st into this world like rain

When in an happy Runic rhyme,

Wherein my youth and dreams and words,

Light as the lavas of summer air

Drowning a wild feeling with the sound

Tempting and dreaming in this passionate light

Filled with deep thoughts of thee.

Brought a silver, silken rest.

Brought a silver silken veil of light,

Beside the dames that gilded each bright noon,

Filled with light of life and light!

Brought down the world to me with their delight;

Put my own solace to a golden light,

Brought a silvery silken veil of light,

Hold about my fingers with their delight,

Divulge this secrets of that lovely isle!

To breathe those voice of thine. The lovely light

Nor ask the riches of the summer air;

To breathe those kisses of the summer air.

Sorrow with its own light eye.

Filled with light of many eyes.

A fountain of light. No living light

Hold about my fingers with their delight

Hold about my fingers as a crown.

Brought on a throne in their elysian air;

To breathe those kisses of the jewelled air;

To breathe those voice of thine.The lovely light

So, the muses definitely wrote…something. It’s not necessarily poetry —yet.

From those lines, I narrowed them down to my favorites in the following lines:

Wield these young honey wine for their delight:

Their shining beauty to each youthful lamp

Splashing the river with a mystic midnight light,

Wherein I feel so certain and happy,

Encircled by a delicate mouth and hand.

Light the world with a mystic motion;

Tempting and dreaming in this passionate light

Brought a silver silken veil of light,

Put my own solace to a golden light,

Brought a silvery silken veil of light,

Hold about my fingers with their delight,

To breathe those kisses of the summer air.

Here, you could put these lines back into the AI to see what you get. I decided to rework them myself to make them less abstract. The lines crossed out above, I ended up using below. I kept my first verse, “feminine beauty dressed in light” and used that as the first line for the poem.

Feminine being dressed in light

To breathe those kisses of the summer air

Held about her fingers my delight

Washed softly away my every care

Encircled by a delicate mouth and hand

Wherein I feel so happy and certain

Her shining beauty imprinted in the sand

She is most deserving of devotion

You don’t have to use all of the lines the muses provided you with. As you can see, I have only used a handful here. This poem isn’t complete, but you get the idea. I’m going to set these lines aside for use with another poem later. The suggestions from the muses in the tool may not have been completely sensible or eloquent, but its a great starting point for poets who may be stuck. It’s also a great way to practice mimicking your favorite classical poet’s writing style if you’d like. Although AI cannot yet write poetry that is indistinguishable from human poetry, it can certainly serve as a useful tool in your own poetry practice.

The next time you find yourself stuck on a line, try using AI to help you finish out your poem! If you try this, leave your work in the comments below! What was your favorite line the muses came up with? Let me know below!

Thank you for reading this blog post and if you’re interested in reading more about AI poetry or delving deeper into the sources I mentioned above, check out the bibliography and further reading sections below! Additionally, if you’d like to read similar posts, check out the related topics section. Lastly, if you want to read more posts from me, check out my recent blog posts.

Bibliography

Saroha, Aditya. “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ can help you write poetry.” The Hindu, November, 28, 2021. (Paragraphs 8 and 10-11).Google, “Verse By Verse” Google AI: Semantic Experiences. (AI Writing Tool and About Section).Hayes, Payton. “Google’s Verse by Verse.” Photos, January, 16, 2023 (Photo Gallery).Holyoak, Keith . “Can AI Write Authentic Poetry?” The MIT Press Reader, December 7, 2022. (Paragraphs 6 and 10).Oxford English Dictionary, third ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), s.v. “artificial intelligence, n.”Danilyuk, Pavel. (@pavel-danilyuk), “Robot Holding a Red Flower.” Unsplash photo," May 28, 2021. (Thumbnail photo).Gupta, Rudrani. “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ Lets You Imitate Writing Style Of Your Favourite Classical Poet.” She The People. November 26, 2020. (Paragraph 4).

Further Reading

“Can a machine write better than you?—5 Best (and worst) AI Poem generators.”by Sara Barkat, September 27, 2022.“How I Use Artificial Intelligence as a Conversation Partner to Write Poetry.” by Lance Cummings, September 9, 2022.“Google’s New AI Helps You Write Poetry Like Poe.” by Matthew Hart, November 24, 2020.“Can AI Write Poetry? — Look at the Examples to Decide.” by Kirsty Kendall, May 4, 2022.“Why Tomorrow’s Poets Will Use Artificial Intelligence.” by Lance Cummings, July 1, 2022.“What Happens When Machines Learn To Write Poetry.” by Dan Rockmore, January 7, 2020.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!25 Strangely Useful Websites To Use For Research and Novel Ideas“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise by Jim SimmermanWriting Exercises from Jeff Tweedy's Book, How To Write One SongHow To Overcome Writer’s BlockWhen Writing Becomes Difficult5 Reasons Most Writers QuitSelf-Care Tips for Bookworms5 Healthy Habits For Every WriterYoga For Writers: A 30-Minute Routine To Do Between Writing Sessions8 Reasons Why Having A Creative Community MattersThe Importance of Befriending Your CompetitionBlank Pages Versus Bad Pages: How To Beat Writer’s BlockKnow The Rules So Well That You Can Break The Rules EffectivelyWriting Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & DisciplineLet’s Talk Amateur Author Anxiety: 7 Writer Worries That Could Be Holding You BackWhy Fanfiction is Great Writing Practice and How It Can Teach Writers to Write WellScreenwriting for Novelists: How Different Mediums Can Improve Your WritingExperimentation Is Essential For Creators’ Growth (In Both Art and Writing)20 Things Writers Can Learn From DreamersCheck out my other Writing Advice and Artificial Intelligence (AI) blog posts!

Recent Blog Posts

Info-Dumping in Science Fiction & Fantasy Novels by Breyonna Jordan

Info-dumping occurs when writers provide excessive background information in a single section, potentially overwhelming readers and disrupting the narrative flow. This issue is prevalent in science fiction and fantasy genres due to their complex world-building requirements. Indicators of info-dumping include lengthy paragraphs, minimal action or conflict, and the author's voice overshadowing the characters'. To avoid this, authors should focus on essential details, integrating additional information gradually as the story progresses. This approach keeps readers engaged without inundating them with information, maintaining a robust and immersive setting.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by, and if you’re a returning reader, it’s nice to see you again! For this post, Breyonna Jordan is taking over the blog to tell you all about info-dumping in science-fiction and fantasy novels! Leave her a comment and check out her website and other socials!

Breyonna Jordan loves exploring new frontiers—underground cities, mythical kingdoms, and expansive space stations, to be exact. As a developmental editor, she relishes every opportunity to help world-builders improve their works and learn more about the wonderful world of writing. She enjoys novels that are fresh, far-reaching, and fun and she can’t wait to see your next book on her TBR list.

Breyonna Jordan is a developmental editor who specializes in science-fiction and fantasy.

What is Info-Dumping?

When writing sci-fi or fantasy, there’s a steep curve on how much the audience needs to know—a world of a curve in fact.

You may have pages and pages of elaborate world histories that readers must be filled in on—the current and past ruling monarchs, failed (or successful) uprisings, how natural resources became so scarce in this particular region, or why a military state exists in this country, but not in the surrounding lands.

Alternatively, you may feel the need to include pages of small details concerning the settings and characters your readers are exploring. While it’s important to include specific details in your writing—the reader can’t possibly know that the night sky features four moons unless you convey these details—oftentimes, the excess exposition can be overwhelming to readers.

This info-dumping can be a pervasive problem in fiction, maybe even the problem that stops you from finding an awesome agent or from obtaining a following on Amazon.

So, below I’ve offered some tips for spotting info-dumping, reasons for and the potential consequences of info-dumping, as well as several tips for avoiding the info-dump.

How Do You Identify Info-Dumping In Your Manuscript?

A section of your work may contain info-dumping if you find:

you are skipping lines while reading (Brotzel 2020),

the paragraphs are very long,

there is little action and conflict occurring,

your voice (and not your characters) has slipped in,

that it looks like it was copied directly from your outline

To help you get a better idea of what excessive exposition can look like, here are two examples of info-dumping from the first chapter of a sci-fantasy manuscript I worked on:

“Hawk was guarding the entrance to the cave while Beetle went for the treasure. These were not their real names of course but code-names given to them by their commander (now deceased) to hide their true identities from commoners who may begin asking questions. Very few people in the world knew their true names and survived to speak it. Hawk and Beetle knew each other’s true names but had sworn to secrecy. They were the youngest people on their team. Beetle was seventeen with silver hair and had a talent for tracking. Hawk was twenty-one with brown hair which he usually wore under a white bandana. He was well-mannered and apart from his occupation in burglary was an honest rule-follower. Beetle and Hawk had known each other since they were children and were as close as brothers.”

“It is one of the greatest treasures in the entire world of Forest #7. This was thought only to have existed in legend and theological transcripts. This Staff was powered by the Life Twig, a mystic and ancient amulet said to contain the soul of Wind Witch, a witch of light with limitless powers.”

Why Do Writers Info-Dump and What Impacts Does It Have On Their Manuscripts?

As a developmental editor who works primarily with sci-fi and fantasy writers, I’ve seen that info-dumping can be especially difficult for these authors to avoid because their stories often require a lot of background knowledge and world-building to make sense.

In space operas, for example, there may be multiple species and planetary empires with complex histories to keep track of. In expansive epic fantasies, multiple POV characters may share the stage, each with their own unique backstory, tone, and voice.

Here are some other reasons why world-builders info-dump:

they have too many characters, preventing them from successfully integrating various traits,

they want to emphasize character backstories as a driver of motivation,

their piece lacks conflict or plot, using exposition to fill up pages instead,

they are unsure of the readers ability to understand character goals, motivations, or actions without further explanation,

they want to share information that they’ve researched (Brotzel 2020),

they want readers to be able to visualize their worlds the way they see them

A Hobbit house with wood stacked out front. Photo by Jeff Finley.

Though these are important considerations, info-dumping often does more harm than good. Most readers don’t want to learn about characters and settings via pages of exposition and backstory. Likewise, lengthy descriptions:

distract readers from story and theme,

encourage the use of irrelevant details,

make your writing more confusing by hiding key details,

decrease dramatic tension by boring the reader,

slow the pacing and immediacy of writing,

prevent you from learning to masterfully handle characterization and description

Think back to the examples listed above. Can you see how info-dumping can slow the pace from a sprint to a crawl? Can you spot all the irrelevant details that detract from the reader's experience? Do you see the impact of info-dumping on the author’s ability to effectively characterize and immerse the reader in the scene?

Info-dumping is a significant issue in many manuscripts. Often, it’s what divides the first drafts from fifth drafts, a larger audience from a smaller one, a published piece from the slush pile.

What Techniques Can Be Used to Mitigate Info-Dumping?

That said, below are three practical tips to help you avoid and resolve info-dumping in your science-fiction and fantasy works:

Keep focus on the most important details. You can incorporate further information as the story develops. This will allow readers to remain engrossed in your world without overwhelming them. It will also help you maintain a robust setting in which there’s something new for readers to explore each time the character visits.

Weave details between conflict, action, and dialogue (Miller 2014). This will allow the reader to absorb knowledge about your world without losing interest or becoming confused. An expansive galactic battle presents the perfect opportunity to deftly note the tensions between races via character dialogue and behavior. A sword fighting lesson can easily showcase new technology (Dune anyone?). A conversation about floral arrangements for a wedding can subtlysubtely convey exposition. Just make sure to keep the dialogue conversational and realistic.

Allow the reader to be confused sometimes. Most sci-fi and fantasy readers expect to be a bit perplexed by new worlds in the earliest chapters. They understand that they don’t know anything, and thus expect not to learn everything at once. Try not to worry too much about scaring them off with new vocabulary and settings. They can pick up on context clues and make inferences as the story progresses. handle it. If you’re still concerned about the amount of invented terminology and definitions, consider adding a glossary to the back matter of the book instead.

Of course, this all raises the question…

Is It Ever Okay to Info-Dump?

You might think to yourself, “I want to stop info-dumping, but it’s so difficult to write my novel without having to backtrack constantly to introduce why this policy exists, or why this seemingly obvious solution won’t end the Faerie-Werewolf War.”

If you’re a discovery writer, it might be downright impossible to keep track of all these details without directly conveying them in text which is why I encourage you to do exactly that.

Dump all of your histories into the novel without restraint. Pause a climactic scene to spend pages exploring why starving miners can’t eat forest fruit or how this life-saving magical ritual was lost due to debauchery in the forbidden library halls.

Write it all down…

Foggy woods illuminated by a soft, warm light. Photo by Johannes Plenio.

But be prepared to edit it down in the second, third, or even fourth drafts.

Important information may belong in your manuscript, but info-dumps should be weeded out of your final draft as much as possible.

Additionally, as I mention often, I am a firm disbeliever in the power and existence of writing rules. There are novels I love that use info-dumping liberally and even intentionally (re: Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy by Douglas Adams). Most classics use exposition heavily as well and they remain beloved by fans old and new.

However, what works for one author may not work for everyone and modern trends in reader/ publisher-preference regard info-dumping as problematic. Heavy reliance on exposition is also connected to other developmental problems, such as low dramatic tension and poor characterization.

If you are intentional about incorporating large swaths of exposition and it presents a meaningful contribution to your work, then info-dumping might be a risk worth taking. If the decision comes down to an inability to deal with description and backstory in other ways then consider reaching out to an editor or writing group instead.

What are some techniques you’ve used to avoid info-dumping in your story? Let us know in the comments!

Bibliography

Brotzel, Dan. “Get On With It! How To Avoid Info Dumps in Your Fiction.” Medium article, February 12, 2020.Finley, Jeff. “Hobbit House.” Unsplash photo, February 28, 2018.Gililand, Stein Egil. “Beautiful Green Northern Lights in the Sky.” Pexels photo, January 7, 2014 (Thumnail photo).Miller, Kevin.“How to Avoid the Dreaded Infodump.” Book Editing Associates article, April 14, 2014.Plenio, Johannes. “Forest Light.” Unsplash photo, February 13, 2018.

Related Topics

Book Writing 101: How To Come Up With Great Book Ideas And What To Do With ThemBook Writing 101: How To Write A Book (The Basics)Book Writing 101: Starting Your Book In The Right PlaceBook Writing 101: How To Choose The Right POV For Your NovelBook Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story PacingBook Writing 101: How To Name Your Book CharactersBook Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent CharactersBook Writing 101: Everything You Need To Know About DialogueHow To Write Romance: Effective & Believable Love TrianglesHow To Write Romance: Enemies-To-Lovers Romance (That’s Satisfying and Realistic)How To Write Romance: 10 Heart-Warming and Heart-Wrenching Scenes for Your Romantic ThrillerHow To Write Romance: Believable Best Friends-To-LoversHow To Write Romance: The Perfect Meet CuteCheck out my other Book Writing 101 and How To Write Romance posts.Book Marketing 101: Everything Writers Need To Know About Literary Agents and QueryingHow To Submit Your Writing To—And Get It Published In—Literary Journals

Recent Blog Posts

“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise by Jim Simmerman